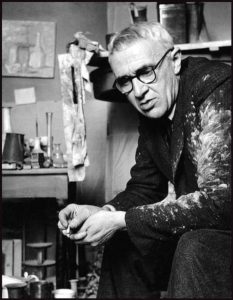

Regular readers of this blog know that Giorgio Morandi is one of the modern artists whose work I love most. I’ve written about him often, most notably here and here, and I’ve long dreamed of owning one of his etchings, a medium of which he was a supreme master. Indeed, I actually dared to bid on a Morandi etching at Sotheby’s in 2003, an experience that left me feeling more or less the way I felt when, long ago, I foolishly sat in with my betters at a Kansas City jam session and got blown off the stand.

Regular readers of this blog know that Giorgio Morandi is one of the modern artists whose work I love most. I’ve written about him often, most notably here and here, and I’ve long dreamed of owning one of his etchings, a medium of which he was a supreme master. Indeed, I actually dared to bid on a Morandi etching at Sotheby’s in 2003, an experience that left me feeling more or less the way I felt when, long ago, I foolishly sat in with my betters at a Kansas City jam session and got blown off the stand.

As I discovered to my chagrin that day, Morandi’s etchings already cost a bit too much in 2003 for me to comfortably afford. Since then their price has gone up even more, and I’ve known for some time that my dream was unlikely to come true. But I kept on hoping for a bargain, and earlier this month I stumbled onto what looked like one. The website that I use to keep up with art at auction informed me that a house in upstate New York had put three Morandi etchings up for sale—all of them for three-figure reserves.

Needless to say, I was suspicious. Small-time auction houses sometimes try to pass off comically obvious Morandi forgeries as authentic, and these etchings were being offered for sale without any information about their provenance save for this homely statement:

The Morandi’s [sic] were consigned by a young plumber working on a house renovation where the buyer’s [sic] instructed the crew to throw all leftover property away; there was a large portfolio containing 16th through 20th century engravings, etchings, lithos, old master drawings, etc. and the Morandi’s [sic] were among those; considering the amount and quality of the portfolio we are confident that these are genuine prints made and signed during the artist’s lifetime.

Yeah, sure, I thought.

Nevertheless, all three etchings looked real at both first and second glances, and the more I thought it over, the more plausible their shared backstory sounded. Who, I asked myself, would go to the trouble of forging an etching by Morandi, then try to sell it at a small-time auction house? Art forgers know far more efficient ways than that to make money.

I pulled my well-thumbed catalogue of Morandi’s etchings off the shelf and went to work. Before long I was satisfied that all three etchings were at the very least based on the real right thing. I e-mailed the auction house to request additional photos, then compared them with photos posted on the websites of museums that own copies of the etchings in question. At length I came to the conclusion that all three etchings were in fact authentic and that the auction house, never before having had occasion to sell a Morandi, simply didn’t know what they were worth.

I pulled my well-thumbed catalogue of Morandi’s etchings off the shelf and went to work. Before long I was satisfied that all three etchings were at the very least based on the real right thing. I e-mailed the auction house to request additional photos, then compared them with photos posted on the websites of museums that own copies of the etchings in question. At length I came to the conclusion that all three etchings were in fact authentic and that the auction house, never before having had occasion to sell a Morandi, simply didn’t know what they were worth.

After talking it over with Mrs. T, I placed modest bids on two of the etchings, one of them my favorite and the other hers. Then I settled down to wait, checking the house’s website at regular intervals. In due course other people placed bids of their own, and I raised my own bids accordingly, gloomily assuring myself that a smart dealer with deep pockets would sooner or later move in for the kill.

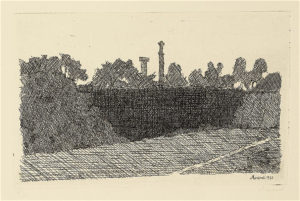

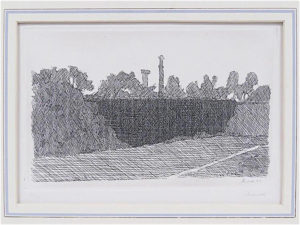

The auction took place on Sunday afternoon, midway through a rehearsal for Billy and Me. I asked the stage manager to call a five-minute break just before the two etchings went on the block, then pulled up the website on my MacBook. I was quickly outbid on the etching that Mrs. T favored, but nobody else bothered to place a higher bid on the one I preferred. The virtual hammer went down, I let out a delighted whoop, my colleagues cheered, and Mrs. T and I were the proud owners of one of fifty known pencil-signed copies of “Veduta della Montagnola di Bologna,” a 1932 landscape portraying a scene from Morandi’s Italian home town. (Another copy of the same etching is owned by New York’s Museum of Modern Art.) What’s more, we knocked it down for the merest sliver of what we would have had to pay for a similar piece at Christie’s or Sotheby’s.

All of Morandi’s etchings are distinguished, but “Veduta della Montagnola di Bologna” stands out among his landscapes. James Panero made particular mention of it in his New Criterion review of the same 2008 show that was my first “in-the-flesh” encounter with Morandi’s graphic oeuvre:

The hatch marks have an all-over effect. Morandi defines his objects entirely through their tone, using a texture of lines woven like linen, reflecting the weave of the printed paper, to darken the areas around and beneath the lemon and bread. In Veduta della Montagnola di Bologna (View of the Montagnola in Bologna, 1932), these textures become more abstracted, largely uniform fields of pattern—a dense but even hatchwork of diagonal, vertical, and horizontal lines for a field in shadow, a more open pattern for areas in sun.

The word “abstracted” is the key. As Morandi himself remarked in a 1955 interview, “I also believe there is nothing more surreal and nothing more abstract than reality.” Looking at “Veduta della Montagnola di Bologna,” which is both self-evidently “realistic” and profoundly, even mysteriously unreal, you can see at once what he meant.

The word “abstracted” is the key. As Morandi himself remarked in a 1955 interview, “I also believe there is nothing more surreal and nothing more abstract than reality.” Looking at “Veduta della Montagnola di Bologna,” which is both self-evidently “realistic” and profoundly, even mysteriously unreal, you can see at once what he meant.

The frustrating thing about being an American fan of Morandi’s work is that you hardly ever get to see it. Even those museums that own paintings by Morandi seldom bother to hang them, and I’ve never seen any of his etchings on display save on the rarest of occasions. Now, though, Mrs. T and I will soon be privileged to look at “Veduta della Montagnola di Bologna” as often as we like. It is a privilege that we will never, ever take for granted.