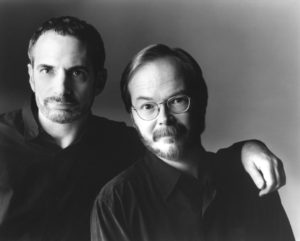

Walter Becker and Donald Fagen, the creative nucleus of Steely Dan, were the Stephen Sondheims of rock, ironic, disillusioned, and musically and lyrically sophisticated to the highest possible degree. I first heard their music (not counting the hit singles from Can’t Buy a Thrill) when The Royal Scam came out in 1976. No sooner did I hear the line “Turn up the Eagles/The neighbors are listening” in “Everything You Did” than I knew that I’d found my rock group. A couple of years later, I bought the original-cast album of A Little Night Music, and that was that: the door of musical adulthood swung wide, never to shut.

Aja, Steely Dan’s next album, came out the following year, at the exact moment when my musical attention had started to shift decisively from rock to jazz. Even so, hearing “Black Cow” and the title track made me realize that rock—some rock, anyway—was still capable of challenging my ear. I vividly remember sitting at a practice-room piano, trying (successfully!) to pick out the intro to “Deacon Blues” and marveling at its harmonic obliqueness. Yet it was definitely rock, not jazz, and I liked that, too. As Becker had explained three years earlier in a Rolling Stone interview, “I’m not interested in a rock-jazz fusion. That kind of marriage has so far only come up with ponderous results. We play rock and roll, but we swing when we play. We want that ongoing flow, that lightness, that forward rush of jazz.”

Aja, Steely Dan’s next album, came out the following year, at the exact moment when my musical attention had started to shift decisively from rock to jazz. Even so, hearing “Black Cow” and the title track made me realize that rock—some rock, anyway—was still capable of challenging my ear. I vividly remember sitting at a practice-room piano, trying (successfully!) to pick out the intro to “Deacon Blues” and marveling at its harmonic obliqueness. Yet it was definitely rock, not jazz, and I liked that, too. As Becker had explained three years earlier in a Rolling Stone interview, “I’m not interested in a rock-jazz fusion. That kind of marriage has so far only come up with ponderous results. We play rock and roll, but we swing when we play. We want that ongoing flow, that lightness, that forward rush of jazz.”

So they did, and they got what they wanted, though not for much longer: Becker’s near-fatal heroin addiction led to the dissolution of Steely Dan, and Fagen soldiered on without him to hugely impressive effect in a pair of solo albums. In time, though, Becker got clean, and Steely Dan reunited in 1993, hitting the road together for the first time in decades and releasing two more albums, Two Against Nature and Everything Must Go, both of them more than up to the high standards that the two men had long since set. Becker also put out a pair of worthy solo albums, 11 Tracks of Whack and Circus Money, which between them gave curious listeners an inkling of his own dark preoccupations.

Still, it was his partnership with Fagen that brought out the best in Becker, and his death on Sunday at the age of sixty-seven moved me in a way that few musical deaths from my own generation have done. Four decades after discovering them, I’m still listening to Steely Dan—and not because they remind me of my own lost youth, either. For me they are not a tired, money-grubbing nostalgia act but the makers of a style of popular music whose artistic vitality and immediacy remain to this day miraculously undiminished by the inexorable passage of time.

Still, it was his partnership with Fagen that brought out the best in Becker, and his death on Sunday at the age of sixty-seven moved me in a way that few musical deaths from my own generation have done. Four decades after discovering them, I’m still listening to Steely Dan—and not because they remind me of my own lost youth, either. For me they are not a tired, money-grubbing nostalgia act but the makers of a style of popular music whose artistic vitality and immediacy remain to this day miraculously undiminished by the inexorable passage of time.

Fagen, who had known Becker since their college days, paid tribute to him this morning in a simple, touching statement:

Walter had a very rough childhood—I’ll spare you the details. Luckily, he was smart as a whip, an excellent guitarist and a great songwriter. He was cynical about human nature, including his own, and hysterically funny. Like a lot of kids from fractured families, he had the knack of creative mimicry, reading people’s hidden psychology and transforming what he saw into bubbly, incisive art.

He will be missed, greatly.

* * *

Walter Becker performs “Down in the Bottom,” a song from 11 Tracks of Whack, in concert: