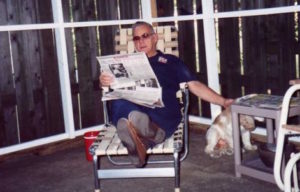

When I was a small boy, I worshipped my father. I was bedazzled by his deep voice, which he loved to raise in song on Sunday drives, and even more by his seeming ability to do, fix, or build anything to which he put his omnicompetent hand. “A thing worth doing, son, is worth doing right,” he would assure me time and again when trying to teach me how to work with tools, not realizing that our ideas of what was worth doing had already started to move in different directions.

When I was a small boy, I worshipped my father. I was bedazzled by his deep voice, which he loved to raise in song on Sunday drives, and even more by his seeming ability to do, fix, or build anything to which he put his omnicompetent hand. “A thing worth doing, son, is worth doing right,” he would assure me time and again when trying to teach me how to work with tools, not realizing that our ideas of what was worth doing had already started to move in different directions.

Not long after he died, I wrote a poem inspired by my father’s miraculous mastery of the mysterious world of things, of which I inherited nary a trace, much to his puzzlement and dismay, though he did manage to pass it on to my similarly gifted brother:

When Dad was on the road alone

And dined, alone, at night,

He wanted everything to be

Not passable, but right:

“A perfect baked potato

Demands the utmost care.

The only way to order steak

Is medium, not rare.”

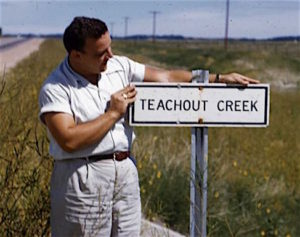

As I grew older, I started to view him in a less favorable light. He was moody, so much so that he could spoil a family gathering without apparent effort simply by emitting a wordless cloud of unexplained dissatisfaction. It never occurred to me at the time that his moodiness might be the outward manifestation of a deep-seated self-doubt, something that had been implanted in him by his imperious mother, for whom nothing he did was ever good enough. All I could see was his own mercurial surface, and I found his emotional vicissitudes to be maddening beyond belief. “The Mighty Teachout Art Players are performing tonight,” I would mutter to my brother whenever he was in a foul temper.

That my father loved us all, though, was never in question. He actually risked his own life to save me from drowning in the Current River one summer, a memory that would later come to mind whenever he did or said something exasperating, which was fairly frequently. In time I learned once more to appreciate him, and came to understand that beneath his surface bluster, he was painfully shy and self-conscious. I suspect—I fear, really—that he was at bottom a frustrated, unhappy man. He would have loved above all things to be rich and successful and to be able to give his children whatever they could possibly want. (As it was, he gave us far more than he could afford.) Instead he was a small-town hardware salesman, and though he did his job faithfully and well, I can’t think of a man less temperamentally suited to his chosen line of work, or one whose secret doubts were more precisely captured in the sad little eulogy that Charley Loman speaks over his own father’s grave in Death of a Salesman: “He’s a man way out there in the blue, riding on a smile and a shoeshine. And when they start not smiling back—that’s an earthquake.”

That my father loved us all, though, was never in question. He actually risked his own life to save me from drowning in the Current River one summer, a memory that would later come to mind whenever he did or said something exasperating, which was fairly frequently. In time I learned once more to appreciate him, and came to understand that beneath his surface bluster, he was painfully shy and self-conscious. I suspect—I fear, really—that he was at bottom a frustrated, unhappy man. He would have loved above all things to be rich and successful and to be able to give his children whatever they could possibly want. (As it was, he gave us far more than he could afford.) Instead he was a small-town hardware salesman, and though he did his job faithfully and well, I can’t think of a man less temperamentally suited to his chosen line of work, or one whose secret doubts were more precisely captured in the sad little eulogy that Charley Loman speaks over his own father’s grave in Death of a Salesman: “He’s a man way out there in the blue, riding on a smile and a shoeshine. And when they start not smiling back—that’s an earthquake.”

Mrs. T, alas, never knew my father at all. To her, he is only a shadowy figure who turns up in family anecdotes, though she’s heard so much about him that she feels almost as if they’d met. As for me, the longer I live, the more I regret not having gotten to know him better. My brother, by contrast, knew him fairly well, unknowable though he ultimately was, and had a relationship with him that was both more stressful and, in the end, far more rewarding. I envy him that.

This is something I wrote a few years ago:

This is something I wrote a few years ago:

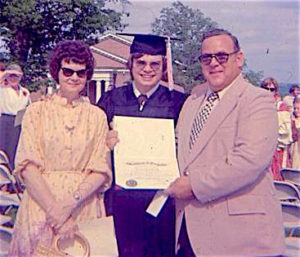

When I started playing piano, I taught myself how to pick out the introduction to Erroll Garner’s version of “Laura,” which I learned from $64,000 Jazz. “Laura,” as it happens, was my father’s favorite song. It would always please him to hear me play it, just as it pleases me that my best friend bears the name of the tune that he loved so much….

He was glad, of course, that I’d taken an interest in the music of his youth, and even more pleased when I started playing it professionally in college. I like to think that he would have been proud of me had he lived long enough to read Pops and Duke. But my father was a difficult man, uneasy in his own skin, and so the two of us never achieved anything remotely approaching intimacy. We simply didn’t have enough in common save for our love of music, though we did manage in the last years of his life to grow somewhat more comfortable with one another. I am—much to my surprise—more like him than I knew.

I cried at his funeral. Two decades later, I think of him nearly every day, and when I do, I remember his other favorite saying: “Too soon we grow old, too late we grow smart.” I wish I’d been smarter about my father sooner, but at least he knew—I hope—how much I loved him.

* * *

Rosanne Cash and John Leventhal perform Cash’s “Black Cadillac”:

Chet Atkins sings “I Still Can’t Say Goodbye,” by James Moore and Robert Blinn: