In 2008 I wrote an essay for National Review about Dragnet. It’s never been reprinted and isn’t available on line, and since I happen to like it a lot, I decided to post it here today. I hope you enjoy it.

* * *

If you’re fifty or older, you won’t need to be told the source of these half-recalled phrases: “The story you are about to see is true.” “This is the city.” “I carry a badge.” “My name’s Friday.” If you’re much younger than that, though, I doubt that you’ll remember Dragnet with any clarity. In the early days of network television, Dragnet was the most successful of all cops-and-robbers TV shows, as well as the most influential. It’s still influential—every episode of Law and Order bears its indelible stamp—but TV has since moved in flashier directions, and I doubt that the narrative conventions brought into being by Jack Webb, the director, producer, and star of Dragnet, will remain conventional for much longer.

If you’re fifty or older, you won’t need to be told the source of these half-recalled phrases: “The story you are about to see is true.” “This is the city.” “I carry a badge.” “My name’s Friday.” If you’re much younger than that, though, I doubt that you’ll remember Dragnet with any clarity. In the early days of network television, Dragnet was the most successful of all cops-and-robbers TV shows, as well as the most influential. It’s still influential—every episode of Law and Order bears its indelible stamp—but TV has since moved in flashier directions, and I doubt that the narrative conventions brought into being by Jack Webb, the director, producer, and star of Dragnet, will remain conventional for much longer.

For baby-boom TV viewers, Dragnet is both iconic and ironic. The version of the show that ran on NBC from 1967 to 1970, in which Webb was partnered by Harry Morgan, was an exercise in unintended self-parody, full of hippy-dippy druggies and the earnest cops who locked them up and threw away the key. A few of the episodes remain effective in their quaint way, but most are embarrassingly stiff. Part of the problem was that Sergeant Joe Friday, Webb’s character, was the squarest of squares, and it was already chic to smirk at such straight-arrow types by the time I reached adolescence. My father watched Dragnet religiously, though, so I did, too, little knowing that what I was seeing each week was a recycled, watered-down simulacrum of the real thing.

The real Dragnet was the black-and-white version that aired from 1951 to 1959. That series, in which Webb was partnered by Ben Alexander, was pulled out of syndication long ago and has never been legitimately reissued on DVD, nor is any “official” version, so far as I know, currently in the works. Fortunately, a few dozen episodes were inadvertently allowed to go out of copyright, and it’s easy to track down copies of them. Madacy Home Video, for instance, offers a budget-priced Dragnet box set containing twenty-five decent-looking public-domain episodes, and you can acquire a dozen more from Shokus Video. At $19.98, the Madacy box is…well, a steal.

Like the later color version, the Dragnet of the Fifties was a no-nonsense half-hour police-procedural drama that sought to show how ordinary cops catch ordinary crooks. The scripts, most of which were written by James E. Moser, combined straightforwardly linear plotting (“It was Wednesday, October 6. It was sultry in Los Angeles. We were working the day watch out of homicide”) with clipped dialogue spoken in a near-monotone, all accompanied by the taut, dissonant music of Walter Schumann. Then and later, most of the shots were screen-filling talking-head closeups, a plain-Jane style of cinematography that to this day is identified with Jack Webb.

Like the later color version, the Dragnet of the Fifties was a no-nonsense half-hour police-procedural drama that sought to show how ordinary cops catch ordinary crooks. The scripts, most of which were written by James E. Moser, combined straightforwardly linear plotting (“It was Wednesday, October 6. It was sultry in Los Angeles. We were working the day watch out of homicide”) with clipped dialogue spoken in a near-monotone, all accompanied by the taut, dissonant music of Walter Schumann. Then and later, most of the shots were screen-filling talking-head closeups, a plain-Jane style of cinematography that to this day is identified with Jack Webb.

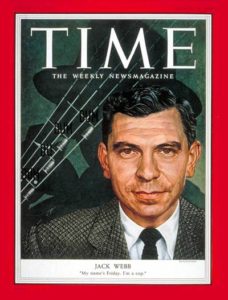

The difference was that in the Fifties, Joe Friday and Frank Smith, his chubby, mildly eccentric partner, stalked their prey in a monochromatically drab Los Angeles that seemed to consist only of shabby storefronts and bleak-looking rooms in dollar-a-night hotels. Nobody was pretty in Dragnet, and almost nobody was happy. The atmosphere was that of film noir minus the kinks—the same stark visual grammar, only cleansed of the sour tang of corruption in high places. But even without the Chandleresque pessimism that gave film noir its seedy savor, Dragnet was still rough stuff, more uncompromising than anything that had hitherto been seen on TV. In 1954 Time called the series “a sort of peephole into a grim new world. The bums, priests, con men, whining housewives, burglars, waitresses, children and bewildered ordinary citizens who people Dragnet seem as sorrowfully genuine as old pistols in a hockshop window.”

The show’s plainness was underlined by the fact that most of the scripts had originally been written by Moser for the radio version of Dragnet, which was launched in 1950. As Michael J. Hayde explains in My Name’s Friday, his excellent biography of Webb, the old scripts were filmed virtually without change when Dragnet moved to TV a year later. Webb believed that there was no need to adapt them more than superficially for the small screen—and he was right. An equally sure instinct led him to cast radio actors in the TV version of Dragnet. He didn’t care how they looked, only how they sounded, and so each episode featured such unfamiliar faces as Vic Perrin, Olan Soulé, and Virginia Gregg, whose unglamorous presence helped make the show seem, in Webb’s words, “as real as a guy pouring a cup of coffee.”

The show’s plainness was underlined by the fact that most of the scripts had originally been written by Moser for the radio version of Dragnet, which was launched in 1950. As Michael J. Hayde explains in My Name’s Friday, his excellent biography of Webb, the old scripts were filmed virtually without change when Dragnet moved to TV a year later. Webb believed that there was no need to adapt them more than superficially for the small screen—and he was right. An equally sure instinct led him to cast radio actors in the TV version of Dragnet. He didn’t care how they looked, only how they sounded, and so each episode featured such unfamiliar faces as Vic Perrin, Olan Soulé, and Virginia Gregg, whose unglamorous presence helped make the show seem, in Webb’s words, “as real as a guy pouring a cup of coffee.”

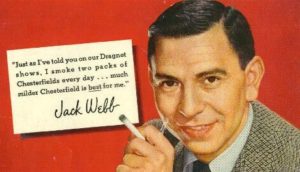

Jack Webb himself was a radio actor who lacked the good looks that would have allowed him to play star parts in Hollywood (his only role of any consequence prior to Dragnet was as William Holden’s best friend in Sunset Boulevard). It was his voice that made him unforgettable: he looked like the second cousin of an aging basset hound, but when he tossed off Moser’s crisp dialogue in a gravelly bass-baritone that reeked of the Chesterfield Kings he chain-smoked on and off screen, you hung on his every word.

Webb was a better actor than the critics knew—and a much better actor in the Fifties than he was in the Sixties. John Dunning’s On the Air: The Encyclopedia of Old-Time Radio contains a penetrating essay on the radio version of Dragnet in which Joe Friday is aptly described as “a cop’s cop, tough but not hard, conservative but caring.” On TV Webb brought out yet another aspect of Friday, the pity he felt for the hapless losers whose paths he crossed each day. But the grueling experience of shooting 276 black-and-white episodes of Dragnet in eight years (plus a 1954 feature film based on the TV series) left its mark on Webb. By 1967 he was burned out on Dragnet, and frustrated that nobody wanted to see him do anything else. Once in a while he turned in a strong performance, but for the most part the new Dragnet was formula-ridden to the point of triteness.

Not so the original series, whose still-undiminished force is far removed from the blandness of the on-screen parody that Curtis Hanson tucked into L.A. Confidential. Hanson’s Badge of Honor mimics Dragnet’s surface mannerisms, but suggests nothing of its hard, laconic essence. While Dan Aykroyd’s affectionate 1987 film spoof was vastly more knowing, Aykroyd’s satirical target was the middle-aged Dragnet of the Sixties, in which Joe Friday and Bill Gannon chased after LSD dealers and took care to read them their rights before slapping on the cuffs. To watch its tougher predecessor is an altogether different experience, especially when Webb rattles off such furious speeches as the one he gave to a crooked policeman in a 1953 episode called “The Big Cop”:

Not so the original series, whose still-undiminished force is far removed from the blandness of the on-screen parody that Curtis Hanson tucked into L.A. Confidential. Hanson’s Badge of Honor mimics Dragnet’s surface mannerisms, but suggests nothing of its hard, laconic essence. While Dan Aykroyd’s affectionate 1987 film spoof was vastly more knowing, Aykroyd’s satirical target was the middle-aged Dragnet of the Sixties, in which Joe Friday and Bill Gannon chased after LSD dealers and took care to read them their rights before slapping on the cuffs. To watch its tougher predecessor is an altogether different experience, especially when Webb rattles off such furious speeches as the one he gave to a crooked policeman in a 1953 episode called “The Big Cop”:

You’ll be all over the front pages tonight and tomorrow morning. Everybody’s gonna read about you. A bad cop. It makes great news. They’re not gonna read about 4,500 other cops. The guys who walked their beats last night. The guys who risked their lives, who did their jobs the way they were trained and the way they’re hired to do….They’re not gonna read about the 98 percent, mister. They’re gonna read about you, one crooked, thieving cop. He worked with a burglary gang. He had an apartment for a beautiful dame and he stole her a fur coat, and he was a cop. And he had a nice wife and two fine children.

You don’t hear speeches like that on television these days, just as you won’t see anything remotely like Dragnet. Today’s TV viewers prefer blow-dried cynicism to gritty idealism. Me, I don’t watch series TV anymore, but I do like to put on an old Dragnet from time to time. I like listening to Jack Webb’s dark-brown voice—and I like to think, whether it’s true or not, that men not entirely unlike Joe Friday are still walking the streets of the anxious city where I live.

* * *

UPDATE: Prints of sixty-four black-and-white public-domain episodes of the original Dragnet are known to survive. Some of them can be viewed on YouTube, and all of them have been transferred to DVD. To order a complete set, go here.

To find out what happened to the other 203 episodes, go here.

* * *

“.22 Rifle for Christmas,” a 1952 episode of Dragnet, written by James Moser and directed by Jack Webb: