I first saw the Gary Burton Quartet on TV when I was in high school. In those days I was finding my way around the illimitably vast world of jazz, searching for a style that spoke to me personally—a jazz that felt as though it were being made for people of my time and place. The rock-inflected jazz that Burton’s group was playing in the late Sixties turned out to be exactly what I was looking for, and ever since then I’ve been a devoted fan.

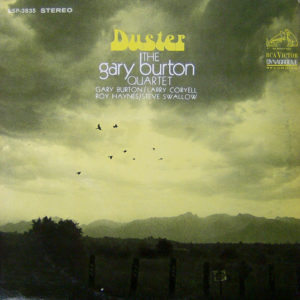

Burton’s playing was already fully formed when the quartet cut its first album, Duster, in 1967. How astonishing to think that he was only twenty-four years old! He would continue to play with the same combination of staggering virtuosity and poised lyricism throughout the half-century to come, just as he continued to bring a steady stream of now-celebrated sidemen, many of them his former students, into his groups. Steve Swallow, Larry Coryell, Pat Metheny, John Scofield, Kurt Rosenwinkel, Julian Lage: all are Burton alumni, and all can testify to his unique gifts. Metheny calls him “the epitome of what a great modern musician should be…a bottomless pit of ideas and melody.”

Burton’s playing was already fully formed when the quartet cut its first album, Duster, in 1967. How astonishing to think that he was only twenty-four years old! He would continue to play with the same combination of staggering virtuosity and poised lyricism throughout the half-century to come, just as he continued to bring a steady stream of now-celebrated sidemen, many of them his former students, into his groups. Steve Swallow, Larry Coryell, Pat Metheny, John Scofield, Kurt Rosenwinkel, Julian Lage: all are Burton alumni, and all can testify to his unique gifts. Metheny calls him “the epitome of what a great modern musician should be…a bottomless pit of ideas and melody.”

I first wrote about Burton in 1981 in the Kansas City Star, back when I was a wet-behind-the-ears working jazz critic. I’ve heard him many times since then, but for some reason it never occurred to me to write about him at length—probably because he was so central a part of my musical life that I took his excellence for granted, foolishly assuming that it, and he, would always be with us. So when I read a story last month in the Miami Herald in which he unexpectedly announced that he would be retiring from public performance at the end of his current concert tour, the news hit me hard, and I resolved to do what I should have done long before.

I sent an e-mail to my editor at The Wall Street Journal and got a thumbs-up in reply, and a week later my heartfelt tribute to Burton appeared in the paper:

Playing with four mallets instead of the long-customary two, a technique that he pioneered, he fills the air with billowing pastel washes of iridescent harmony, miraculously transforming a percussion instrument into a font of cool, silvery lyricism. Watching him manipulate his mallets at something approaching Mach 2 feels a bit like chatting with a member of a more highly evolved species.

No sooner did I start writing the piece than it occurred to me to find out whether Burton was stopping in New York on his last tour. I checked his website and saw that he and the pianist Makoto Ozone, who has worked with him off and on for the past thirty-five years, were coming to Birdland. It was the worst possible weekend for me to sandwich in a nightclub visit—I’d scheduled back-to-back shows on Friday, Saturday, and Sunday—but I knew I’d hate myself if I missed Burton’s final gig in New York, so I booked a seat for the last set on Saturday, and returned to the theater district that night after fortifying myself with a post-matinée catnap.

Time was when Birdland was one of my regular haunts, so much so that I’ve been present when two live albums were recorded there. Back then, though, I was going out on the town four or five times a week in my self-defined capacity as flâneur-of-all-trades, reporting on the arts in New York each month for the Washington Post. Then I became a full-time drama critic and, not long afterward, a happily married man who divides his time between New York and rural Connecticut. Soon I found that I no longer had the time or inclination to go to clubs other than occasionally. It wasn’t that I loved jazz any less, but my newfound passion for theater was now central to my life, and I felt the growing need to devote my energies to what mattered most to me. When I showed up at Birdland at ten p.m. on Saturday, an hour when I’m usually looking for a cab to take me home from a Broadway show, it struck me that I couldn’t recall the last time I’d been there.

Fortunately, the place is still the same, as is the tasty Cajun-style cooking that has long distinguished Birdland, and no sooner did I settle into my second-row seat and order a plate of jambalaya than I felt as if I’d never been away. In due course Burton and Ozone made their entrance and went to work. I was catapulted into the moment, reveling in the artistry of a great musician whom I knew I would never again see on stage.

Fortunately, the place is still the same, as is the tasty Cajun-style cooking that has long distinguished Birdland, and no sooner did I settle into my second-row seat and order a plate of jambalaya than I felt as if I’d never been away. In due course Burton and Ozone made their entrance and went to work. I was catapulted into the moment, reveling in the artistry of a great musician whom I knew I would never again see on stage.

Burton, who has undergone six heart operations, is retiring at seventy-four because he feels that his playing has started to show the corrosive effects of age and illness. “It increasingly makes me uncomfortable when I go out on stage and I don’t feel as confident that I’m going to have a great night,” he explained in the Miami Herald. “I’m starting to have moments—what we call senior moments. I have them sometimes when I’m playing. I suddenly forget where I am in the song.” All true, no doubt, but you couldn’t have proved it by me, or anyone else at Birdland, on Saturday. He played a demanding set with an unmistakably valedictory air: Charlie Christian’s “Air Mail Special,” Chick Corea’s “Brasilia,” Swallow’s “Eiderdown,” Antônio Carlos Jobim’s “O Grande Amor,” Ozone’s “Times Like These,” Scofield’s “Why’d You Do It?” and two standard ballads, “Beautiful Love” and “For Heaven’s Sake.” All were tossed off with miraculous ease and flair, and when he tore into an arrangement for vibraphone and piano of a Scarlatti sonata, his mallets flew so fast that all you could see at the end of his hands was a mystifying blur.

I wondered how the famously matter-of-fact Burton would call it quits at evening’s end. Sure enough, he steered clear of pathos and pulled a gratifying and characteristic surprise out of his hat: Paquito d’Rivera, the jazz clarinetist, and Joseph Alessi, the principal trombonist of the New York Philharmonic, joined him and Ozone on stage for a hard-swinging jam on “Bags’ Groove,” a well-worn, well-loved blues riff by Milt Jackson, the other great modern-jazz vibraphonist of the twentieth century. Then it was all over at last, and Burton left the bandstand and was swamped by admirers.

I wondered how the famously matter-of-fact Burton would call it quits at evening’s end. Sure enough, he steered clear of pathos and pulled a gratifying and characteristic surprise out of his hat: Paquito d’Rivera, the jazz clarinetist, and Joseph Alessi, the principal trombonist of the New York Philharmonic, joined him and Ozone on stage for a hard-swinging jam on “Bags’ Groove,” a well-worn, well-loved blues riff by Milt Jackson, the other great modern-jazz vibraphonist of the twentieth century. Then it was all over at last, and Burton left the bandstand and was swamped by admirers.

It happens that I know Burton a bit, well enough that he made a point of coming to the opening of my Palm Beach Dramaworks production of Satchmo at the Waldorf last year, a gesture that filled me with pride. We’re nothing like old friends, though, and I didn’t want to force myself on him at what I felt sure would be an emotional moment, so I contented myself with sending a congratulatory e-mail when I got home. “You couldn’t possibly have left us on a higher note,” I wrote. The next morning his response was in my mailbox: “I feel really great going out on top of my game, or close to it, anyway.” So he did: I’ve never heard him play better. That is how I will always remember Gary Burton, as a silver-haired septuagenarian playing with the sacred fire and total assurance of a young man with his whole life ahead of him. We should all go out like that.

* * *

The Gary Burton Quartet plays Makoto Ozone’s “Times Like These” in 1989:

Gary Burton’s very first recording as a studio sideman, Floyd Cramer’s “Last Date,” recorded in Nashville in 1960: