This essay about John P. Marquand’s Point of No Return originally appeared in National Review in 2009. It’s never been reprinted, nor has it been available on line until now. I post it in order to draw your attention to a little-remembered book that I consider to be one of the most noteworthy American novels of the twentieth century.

This essay about John P. Marquand’s Point of No Return originally appeared in National Review in 2009. It’s never been reprinted, nor has it been available on line until now. I post it in order to draw your attention to a little-remembered book that I consider to be one of the most noteworthy American novels of the twentieth century.

* * *

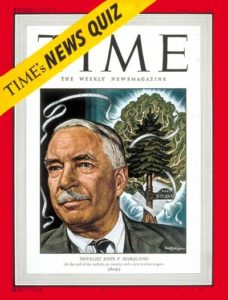

Is there an American novelist who has fallen farther from grace than John P. Marquand? For years he was one of the best-known names on the best-seller lists, and his part-time job as a judge for the Book-of-the-Month Club made him as influential as he was successful. But Marquand wasn’t a hit with the highbrows. Edmund Wilson, writing in the New Yorker in 1942, went so far as to declare that “Mr. Marquand hasn’t the literary vocation.” Marquand was stung by such sniping, and despite his Pulitzer Prize and Time cover, he went to his grave sure that he’d gotten the shaft because he was popular. True or not, it was Wilson who had the last word. Only two of Marquand’s melancholy, satire-flecked novels of middle- and upper-middle-class life, The Late George Apley (1937) and H.M. Pulham, Esquire (1941), are still in print, and despite the efforts of a handful of stalwart critical admirers, he is now all but forgotten.

The latter-day eclipse of Marquand’s reputation is explicable, if not quite understandable. He was a Trollope-like chronicler of New England manners who lacked Trollope’s charm, and his smoothly flowing prose was more workmanlike than stylish. Solid competence, not arresting individuality, was his literary line. Yet several of his books had the root of the matter in them, and one in particular strikes me as little short of masterly. Point of No Return, published in 1949, is the story of an ambitious young boy from a small town in Massachusetts who makes his way to Manhattan, there to become the vice president of a small private bank—and to find that the promotion he has sought since returning from the war is mysteriously unfulfilling.

If any of this sounds suspiciously familiar, it’s because Marquand was one of the first novelists to explore the lingering disquiet felt by a generation of American businessmen whose lives were upended by World War II. Charles Gray, the protagonist of Point of No Return, was the original man in the gray flannel suit, unable to see why the world he left behind was no longer capable of satisfying him. But Point of No Return is not the novelistic equivalent of The Best Years of Our Lives. It is, rather, something more complicated and searching: a study of success and its discontents.

America’s major novelists have had surprisingly little to say about the world of work, save to dismiss it from a distance as soul-shriveling drudgery. Point of No Return, by contrast, opens with a detailed and wholly believable description of a day in the life of Charles Gray, who takes the 8:30 train to Manhattan each morning, there to labor in the vineyards of the Stuyvesant Bank, where he clips the coupons of rentiers and polishes such apples as come his way. At night he returns home to his wife, children and country club, balances the checkbook, and dreams of the promotion that will make it possible for him to send his son to Exeter. Then he awakes one rainy morning and finds himself thinking instead of Clyde, the Massachusetts village that he left behind in 1930 to seek his fortune. All at once Charles gazes into his bathroom mirror and sees that the values by which he lives are “contrived.” His friends are Babbitts, his daily chores meaningless, his ambitions hollow. He wants something more—but what?

With the practiced skill of a Hollywood director, Marquand turns the clock back a quarter-century. We learn that Charles is the oldest son of a New England family headed by a flighty, unsound man who frittered away a small fortune and thereafter was viewed with suspicion by his ultra-proper friends and neighbors. When Charles falls in love with the daughter of one of Clyde’s oldest families, he discovers that his father’s irresponsibility has cast a cloud over his own reputation and that he is not deemed an acceptable suitor. Cruelly hurt by his inability to vault the high walls of caste, he puts Clyde behind him, goes to New York, and seeks a less provincial life. For a time he thinks he has found it, but then he looks into the mirror and realizes that he has spent the whole of his life measuring himself by the yardstick of a town that time has left behind. Not even the promotion he has sought for so long can erase the chilling suspicion that his worldly success is a handful of dust:

With the practiced skill of a Hollywood director, Marquand turns the clock back a quarter-century. We learn that Charles is the oldest son of a New England family headed by a flighty, unsound man who frittered away a small fortune and thereafter was viewed with suspicion by his ultra-proper friends and neighbors. When Charles falls in love with the daughter of one of Clyde’s oldest families, he discovers that his father’s irresponsibility has cast a cloud over his own reputation and that he is not deemed an acceptable suitor. Cruelly hurt by his inability to vault the high walls of caste, he puts Clyde behind him, goes to New York, and seeks a less provincial life. For a time he thinks he has found it, but then he looks into the mirror and realizes that he has spent the whole of his life measuring himself by the yardstick of a town that time has left behind. Not even the promotion he has sought for so long can erase the chilling suspicion that his worldly success is a handful of dust:

There was a weight on Charles again, the same old weight, and it was heavier after that brief moment of freedom. In spite of all those years, in spite of all his striving, it was remarkable how little pleasure he took in final fulfillment. He was a vice-president of the Stuyvesant Bank. It was what he had dreamed of long ago and yet it was not the true texture of early dreams….They would sell the house at Sycamore Park and get a larger place. They would resign from the Oak Knoll Club. And then there was the sailboat. It had its compensations but it was not what he had dreamed.

What keeps Point of No Return from descending into romance-novel bathos is the cool detachment with which Marquand describes Charles Gray’s failed quest for fulfillment. Though he is sensitive, intelligent, and deeply dissatisfied, none of these things propels him out of the tightly circumscribed orbit of his businessman’s life. Instead of having a torrid affair with his secretary or quitting the Stuyvesant Bank to become a beachcomber, he stays loyal to his wife and children, and we never doubt that he will continue to remain so, or that his steadfastness is anything other than admirable, perhaps even wise. What he has is all there is.

Most people who read for pleasure sooner or later find themselves in the pages of a novel. When I first read Point of No Return, I was stuck by the precision with which it conveys what it feels like to partake of an experience that was and is central to American life. Anyone who, like me, has traveled the long road that leads from a small-town childhood to a big-city career will immediately appreciate the way in which Marquand sketches Charles’ transformation into a polished banker. To be sure, Point of No Return is no Horatio Alger tale—Charles Gray is too riddled with self-doubt for that—but neither is its author cynical about the circuitous voyage that is his subject. The Great Gatsby tells a similar story more artfully, but also with a heightening touch of melodramatic lyricism that is necessarily less true to life. Not so the plainer-spoken Marquand. Writing in 1949, he suggested with uncanny exactitude much of what I felt when I came to New York as a young man some three decades later.

I especially like the scene in which Charles arrives at Grand Central Station in 1930, having put his troubled past behind him to come looking for a job:

Outside the station, the streetcars and the traffic were already running in a steady stream under the ramp at Pershing Square. The shops on Forty-Second Street, the drugstores, the optical stores and haberdasheries, were already opening for the day….As he walked up the Avenue the city seemed to him as impersonal as it always did later and he loved that impersonality. Now that he had left his bag at the parcel room there was nothing to tie him. The tides of the city moved past him and he was part of the tide. His own problems and his own personality merged with it.

In The Message in the Bottle, Walker Percy compared Charles’s “exurbanite alienation” to the sweaty desperation of Franz Kafka’s antiheroes. Though he also spoke of Marquand’s “Book-of-the-Month Club disenchantment” as being restricted by “the genteel limits of irony,” he praised Gray as “the suburban counterpart of Joseph K. (and in my opinion, a not unworthy counterpart: the first hundred pages of Point of No Return are of a very high order).” I used to think that was coming it a bit high. Now I know better. Point of No Return is not a great novel, nor was its author a great novelist, but I’ve yet to read a book that did a better job of putting of a man like Charles Gray on paper.

Therein lies the power and the significance of Point of No Return: it portrays middle-class life with a sympathetic honesty that is both unromantic and uncommon. When Charles admits to himself that his destiny is “to face no danger or uncalculated risk….to measure his merriment and hedge on his tragedies,” he is telling most of us something about ourselves as well—something that we don’t really want to hear, even though we wouldn’t have it any other way.