It’s unusual for me to write pieces that don’t see print, but back in the days when I was covering classical music and dance for Time, the press of breaking news would occasionally knock me “out of the book.” That happened when I wrote about Mikhail Baryshnikov, whom I’d seen on stage many times but never met, in 1998. The occasion was his fiftieth birthday, which he celebrated by giving a series of solo concerts, his first in America. In those days Time considered such things sufficiently important to send me to interview him at his Manhattan apartment. Here’s how star-struck I was: when I got there, I looked at his mailbox to see if his full name was on it. (It was.)

I wrote what I thought was a pretty good piece. Alas, it was scheduled to run on the same week that it became known that President Clinton had had a fling with Monica Lewinsky, and so it was killed. If memory serves, it ran in the Latin American edition of Time, but nowhere else.

I wrote what I thought was a pretty good piece. Alas, it was scheduled to run on the same week that it became known that President Clinton had had a fling with Monica Lewinsky, and so it was killed. If memory serves, it ran in the Latin American edition of Time, but nowhere else.

I did review Baryshnikov’s City Center concert for the New York Daily News that same week:

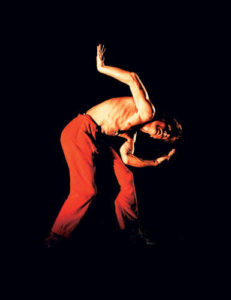

No matter what he’s dancing, Mikhail Baryshnikov fills his space to overflowing, and to see him perform alone is to witness one of the few indisputable miracles that contemporary dance has to offer.

But my Time piece was relegated to my files, and I didn’t even think about it again until the other day, when someone on Twitter asked the world a wonderful question: Who’s the coolest person you’ve ever interviewed? All at once I remembered my Interview That Never Ran, and found that I still had an electronic copy. Here it is, in its entirety. I hope it amuses you.

* * *

Once Mikhail Baryshnikov was as pretty as a ballerina, and soared through the air with heedless grace. Now age has peeled the prettiness from his bony face, just as three decades’ worth of jumps and turns have left their cruel marks on his small, wiry body. But even after five knee operations, the greatest dancer of our time, who turns 50 on Jan. 27, is still dancing—brilliantly. “Fifty is just a date,” Baryshnikov says. “It doesn’t mean anything.” He’ll be proving it this week at New York’s City Center, when he gives his first American solo recital ever.

Why solo? Why now? “Why not?” Baryshnikov replies cheerily, in a soft voice whose every vowel is redolent of the former Soviet Union, from which he defected in 1974 (and to which he returned for the first time last October, dancing a solo concert in Riga, his birthplace). “I’ve been working on solo repertory for many years with different choreographers, and a few years ago I first had the idea to try to do a full evening of solos. It sort of keeps me happy, and keeps me on my toes, keeps me in shape.”

What keeps Baryshnikov on his toes today, to be sure, are not the high-flying classical ballet roles that made him the most famous male dancer since Rudolf Nureyev. For the past seven years, he has led a small troupe, the White Oak Dance Project, which performs the works of such noted modern-dance choreographers as Mark Morris, Twyla Tharp and Merce Cunningham; his City Center program will feature Morris’ “Three Russian Preludes” and the world premiere of “HeartBeat: mb,” a dance by Sara Rudner and Christopher Janney accompanied not by the yearning strings of Tchaikovsky, but the amplified sounds of Baryshnikov’s heart.

What keeps Baryshnikov on his toes today, to be sure, are not the high-flying classical ballet roles that made him the most famous male dancer since Rudolf Nureyev. For the past seven years, he has led a small troupe, the White Oak Dance Project, which performs the works of such noted modern-dance choreographers as Mark Morris, Twyla Tharp and Merce Cunningham; his City Center program will feature Morris’ “Three Russian Preludes” and the world premiere of “HeartBeat: mb,” a dance by Sara Rudner and Christopher Janney accompanied not by the yearning strings of Tchaikovsky, but the amplified sounds of Baryshnikov’s heart.

Nor does his dancing look the same as it did in the days when his appearances in Giselle and Don Quixote filled the Metropolitan Opera House with starry-eyed fans. “I dance the way my body understands,” he says matter-of-factly. “When choreographers make dances on me now, they know that I cannot be much in the air and I cannot be much to the floor because of certain physical problems—my knee, you know. Which means I am somewhere in the middle. They know my register, my octave. But I feel 100% at home in this octave. Maybe I cannot take high C anymore, but I know exactly what I can do.”

The challenge of sustaining what he reckons to be “an hour of pure solo dancing” would be daunting for a man half Baryshnikov’s age. But once the curtain goes up, everything snaps into place: “The evening goes really fast for me. At the end, I’m sort of losing sense of time, and it floats. The hours before the show, they’re sometimes dragging, I’m sort of nervous, trying to get away from all these negative thoughts, insecurity, anxiety.”

Baryshnikov’s decision to give up classical ballet is, he says, final. “I can still do a few classical pieces very easily,” he explains pensively, “but there’s no time left. My life is almost over. I believe in family genetics, and I feel that to put together amount of years that my mother and father lived in this world and divide by two—the difference, you know, it’s not much. So I am working now just for total pleasure. It is not a job, it’s not for money. It keeps me scared. Because I like to get scared. I like to get nervous. To go in front of people…it’s fun.” A smile crackles across his face, and he speaks in the plummy tones of a circus barker: “Come to see Grandpa dance! Ho, ho, ho!”

Some of the fans who flock to City Center to see Grandpa Misha dance (he will also be performing in Los Angeles, Escondido and Santa Barbara next month) will surely be startled by the rigor and austerity of the modern works he now espouses so compellingly. But Baryshnikov has always been the most curious of the great dancers, and his boundless curiosity, as he well knows, is no small part of what makes him great. It was what made him take his life in his hands and break away from his KGB guards in Toronto a quarter-century ago; it is what makes him submit to the sometimes painful demands of choreographers who were still in diapers when he took his first curtain call. “I try to digest the best influences, the best moves and mannerisms, of other dancers whom I highly, highly admire, and I try to make all those elements my own,” he says. “But I’m also just trying to be myself on stage. Just me, nobody else. And that’s enough—if it works.” It always has.

* * *

A rare home video of a 1998 performance by Mikhail Baryshnikov of Sara Rudner’s “HeartBeat: mb.” The venue and performancedate are unknown:

Baryshnikov receives a Kennedy Center Honor in 2000. The presenter is Gregory Hines: