In today’s Wall Street Journal “Sightings” column I write about surviving sound recordings of the speaking voices of men and women born in the nineteenth century. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

In 1931, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., the oldest person ever to sit on the U.S. Supreme Court, turned 90. By then the seemingly ageless judge was widely regarded as a national treasure, so CBS marked the occasion with a prime-time birthday tribute in which he spoke briefly from his home in Washington, D.C. Justice Holmes was the most eloquent jurist this country has yet produced, and he rose to the near-final occasion (he retired from the bench ten months later and died in 1935) with characteristic grace, closing by quoting his own elegant translation of a passage from a medieval poem in praise of wine, women and song that he bent to his own austere purposes. “To live is to function,” he said. “That is all there is to living. And so I end with a line from a Latin poet who uttered the message more than fifteen hundred years ago: ‘Death plucks my ear and says, Live—I am coming.’”

Three years ago the Harvard Law School Library, where Holmes’ papers are housed, launched an online “digital suite” (library.law.harvard.edu/suites/owh) that allows anyone with a computer to access its digitized 100,000-document collection of Holmesiana. I knew from having read G. Edmund White’s 2006 biography that the 1931 radio broadcast was recorded off the air and that the Harvard Law School Library, where Holmes’ papers are housed, possessed a tape copy of the recording. Why, I wondered, wasn’t it possible to use the Holmes Digital Suite to listen to that 1931 aircheck?

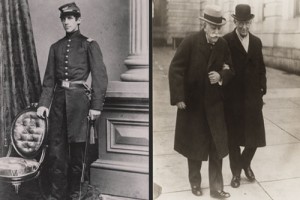

I got in touch with Harvard a few months ago and suggested that they post the broadcast online, and now they’re done so. Go here and you’ll be able to listen to a RealAudio copy. To read what Holmes said on that long-ago evening is to be stirred to the marrow. But to actually be able to hear it—to listen to the tremulous yet dignified voice of a man who met Abraham Lincoln and was wounded three times in the Civil War, then spent the better part of three decades sitting on the U.S. Supreme Court—is an experience of another order altogether.

I got in touch with Harvard a few months ago and suggested that they post the broadcast online, and now they’re done so. Go here and you’ll be able to listen to a RealAudio copy. To read what Holmes said on that long-ago evening is to be stirred to the marrow. But to actually be able to hear it—to listen to the tremulous yet dignified voice of a man who met Abraham Lincoln and was wounded three times in the Civil War, then spent the better part of three decades sitting on the U.S. Supreme Court—is an experience of another order altogether.

In case you neglected to do the math, Justice Holmes was born in 1841. That makes him one of a significant number of notable men and women born in the 19th century whose voices were recorded for posterity. So far as is known, the earliest-born person to have left behind a sound recording of his speaking voice was Alfred Tennyson, who was born in 1809, the same year as Lincoln and Felix Mendelssohn. He recorded several of his poems in 1890 on a machine borrowed from Thomas Edison, and one of them, “The Charge of the Light Brigade,” can be easily found on YouTube. So can the voices of, among others, Max Beerbohm, Sarah Bernhardt, Robert Browning, G.K. Chesterton, Mahatma Gandhi, O. Henry, James Joyce, Rudyard Kipling, Vladimir Lenin, H.L. Mencken, Florence Nightingale, Theodore Roosevelt, George Bernard Shaw, Leo Tolstoy (speaking in English!), Booker T. Washington, Woodrow Wilson and W.B. Yeats….

To hear these antique recordings, near-opaque though some of them are, is at once mysterious and moving…

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

Alfred Tennyson reads “Charge of the Light Brigade” in 1890: