A week after bringing home my new MacBook Air, I’m more or less used to it. To be sure, I have yet to explore any of its more recherché capabilities, but now that I’ve written two Wall Street Journal columns and sent and received hundreds of e-mails, I feel confident of my ability to carry on my usual computer-related activities in a recognizably normal way, which is what really matters to a journalist who spends most of any given day plugged into the great world of cyberspace.

A week after bringing home my new MacBook Air, I’m more or less used to it. To be sure, I have yet to explore any of its more recherché capabilities, but now that I’ve written two Wall Street Journal columns and sent and received hundreds of e-mails, I feel confident of my ability to carry on my usual computer-related activities in a recognizably normal way, which is what really matters to a journalist who spends most of any given day plugged into the great world of cyberspace.

Therein lay the source of the anxieties that kept me from switching computers sooner: I didn’t know that I wouldn’t have to learn anything dramatically new in order to use my MacBook Air. Yes, it’s much faster and has a far more powerful battery than its predecessor, but there’s an essential continuity between Old Laptop and New Laptop. To put it another way, my life isn’t significantly different from the way it was last week—it’s just easier.

This distinction isn’t as widely understood as it should be. Most new technologies make our lives easier without changing them other than superficially. The compact disc, for example, was a convenience, not a revolution. Unlike the iPod, it didn’t alter our relationship to the world of music. The answering machine, by contrast, really did transform the way in which we used the telephone by making it possible to screen incoming calls. As soon as that possibility became a reality, the place of the telephone in daily life underwent a profound change, and never changed back.

This distinction isn’t as widely understood as it should be. Most new technologies make our lives easier without changing them other than superficially. The compact disc, for example, was a convenience, not a revolution. Unlike the iPod, it didn’t alter our relationship to the world of music. The answering machine, by contrast, really did transform the way in which we used the telephone by making it possible to screen incoming calls. As soon as that possibility became a reality, the place of the telephone in daily life underwent a profound change, and never changed back.

Not everyone is open to such change. Sooner or later each generation comes to a great technological divide, a chasm that most of its aging members are unable or unwilling to cross. For my mother, who was born mere weeks before the Great Depression, that chasm was the invention of the personal computer. She owned an answering machine—I bought it for her—but she never screened her calls, nor did she learn how to use a computer. When the PC became a routine part of American life, she was officially old. The world had passed her by.

I was born in 1956, twenty-seven years after my mother, which means that I lived through the early years of the rise of personal computing. Indeed, my initial exposure to screen-based electronic word processing, as I recalled in this space eleven years ago, came long before I managed to save up enough money to buy my first IBM desktop computer:

I was born in 1956, twenty-seven years after my mother, which means that I lived through the early years of the rise of personal computing. Indeed, my initial exposure to screen-based electronic word processing, as I recalled in this space eleven years ago, came long before I managed to save up enough money to buy my first IBM desktop computer:

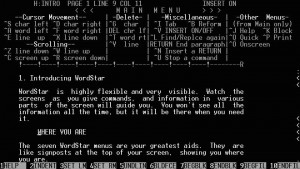

I first used a computer for word processing some time around 1979, when the Kansas City Star told me that I had to start writing my concert reviews directly on its mainframe computing system rather than typing them on an IBM Selectric and having them scanned into the system optically. I was stunned—that really is the word for it—by my first encounter with word processing, and recognized at once that it would change every writer’s life for the better. I first used a personal computer in 1985, when I started writing my pieces on the PC of Harper’s Magazine after hours (and not infrequently on company time, too!). I bought an identical IBM computer two years later when I went to work for the New York Daily News, and used it for the next decade and a half.

Needless to say, I was right. Personal computers transformed the working habits of every writer who, like me, chose to use them. But they did much more than that: they upended the daily lives of everyone who, unlike my mother, was young enough to leap across the technological chasm and embrace their revolutionary power. No day passes when I am not grateful for having been born in time to join that revolution.

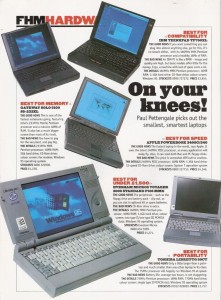

The next major upheaval in my computing life came in 1995, when I bought my first laptop. By then I’d started working in earnest on The Skeptic, my H.L. Mencken biography, and it wasn’t long before I figured out that I was going to need to use a laptop in order to transcribe unpublished passages from Mencken’s papers, most of which he had deposited in Baltimore’s Enoch Pratt Free Library and which I couldn’t examine anywhere else.

The next major upheaval in my computing life came in 1995, when I bought my first laptop. By then I’d started working in earnest on The Skeptic, my H.L. Mencken biography, and it wasn’t long before I figured out that I was going to need to use a laptop in order to transcribe unpublished passages from Mencken’s papers, most of which he had deposited in Baltimore’s Enoch Pratt Free Library and which I couldn’t examine anywhere else.

The machine I bought was a chunky gray slab of plastic that was similar in size and weight to an old-fashioned Sears Christmas catalogue. Elegant it wasn’t, but it made it possible for me to input material from the Mencken Collection on the spot, as well as to write in hotel rooms and on planes and trains. What had once been impossible soon became essential, and in due course my professional life underwent yet another upheaval: I scrapped my desktop computer (and, perhaps not coincidentally, my landline) shortly after the twentieth century gave way to the twenty-first. Compared to that giant step, buying a MacBook Air was more like buying a new car.

So when will I arrive at my own great divide? Since I have yet to acquire a smartphone, some might say that it’s already here, but I know better. I’ve never been an early adopter—I prefer to let others work out the bugs—and so I deliberately chose not to buy an iPhone until after I’d finally gotten a new laptop and familiarized itself with its idiosyncratic workings. Having done so without incident, I expect I’ll make the Next Bold Leap Forward some time in the next month or two. And after that? I don’t doubt that a time will come when I no longer feel equal to the task of keeping up with technological change, but my guess is that dread day of reckoning is still a long way off.

It helps that I’ve never been scared by the prospect of change. In 2005 I blogged about some of the technologies that I’d already outlived—typewriters, fax machines, black discs, snail mail—and marveled at the vertiginous velocity of their onrushing obsolescence. What surprises me in retrospect about that posting is that I already took for granted the fact that I no longer had a landline, so much so that I didn’t even bother to mention it. That’s what it means to live in an age of constant change: you take the damnedest things for granted.

It helps that I’ve never been scared by the prospect of change. In 2005 I blogged about some of the technologies that I’d already outlived—typewriters, fax machines, black discs, snail mail—and marveled at the vertiginous velocity of their onrushing obsolescence. What surprises me in retrospect about that posting is that I already took for granted the fact that I no longer had a landline, so much so that I didn’t even bother to mention it. That’s what it means to live in an age of constant change: you take the damnedest things for granted.

All of which reminds me that I didn’t write a word during the four days that I spent without a computer. Strange as it may sound, that didn’t bother me in the least. In fact, I rather enjoyed it. What really irked me was that I had to call a restaurant to make a dinner reservation instead of using OpenTable. Somehow I find that encouraging.

* * *

A 1977 TV ad for IBM’s first portable computer:

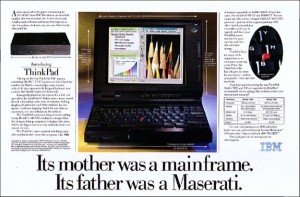

An IBM ThinkPad commercial from the Nineties: