When Peggy Crosno Presson, my late mother’s youngest sister, died in March, the members of the Crosno family who made their way to southeast Missouri for her funeral all said the same thing, more or less: How come we never see each other any more except at funerals? I wasn’t able to be there—I couldn’t take time off from my duties on Broadway—but when David, my brother, reported the conversation to me on the phone that night, I knew just what they’d meant. Years had gone by since the Crosnos last held a reunion, and the time for doing so was growing short. Not only have all but one of my mother’s brothers and sisters passed away, but I unexpectedly and grievously lost one of my first cousins two and a half years ago.

David is a man of action, so he and Kathy, my sister-in-law, decided on the spot to organize a large-scale family gathering. E-mails were duly sent out, schedules collated, and plans made, the end result of which was that twenty-nine members of our far-flung clan traveled last Saturday morning to Smalltown, U.S.A., to break bread in the half-century-old ranch house where David and I grew up and where he and Kathy now live.

David is a man of action, so he and Kathy, my sister-in-law, decided on the spot to organize a large-scale family gathering. E-mails were duly sent out, schedules collated, and plans made, the end result of which was that twenty-nine members of our far-flung clan traveled last Saturday morning to Smalltown, U.S.A., to break bread in the half-century-old ranch house where David and I grew up and where he and Kathy now live.

Much has happened to 713 Hickory Drive in the three years since the death of my mother. My brother remodeled the house close to singlehandedly, and I saw most of his virtuoso handiwork for the first time when I arrived on Thursday. Not immediately, though, for no sooner did I pull into the driveway than the storm alarms inside the house went off, a tornado warning having just been issued by the U.S. Weather Service. It was no great surprise: we get a fair number of tornadoes in southeast Missouri, one of which touched down a few hundred yards from my brother’s first house in 1986.

Fortunately, this storm, unlike its predecessor, passed us by with room to spare, and once it did so, David and Kathy took me through the house, both of them bursting with a mixture of hard-earned pride and understandable anxiety. Had they changed too many things? I’d long since made it as clear as I possibly could that I wanted them to please themselves, not me, but that didn’t stop them from worrying. They didn’t need to. Old and new had been sensitively blended together, and the results were all I’d hoped for and more. “I only wish Mom had lived to see it,” I said, meaning every word.

Fortunately, this storm, unlike its predecessor, passed us by with room to spare, and once it did so, David and Kathy took me through the house, both of them bursting with a mixture of hard-earned pride and understandable anxiety. Had they changed too many things? I’d long since made it as clear as I possibly could that I wanted them to please themselves, not me, but that didn’t stop them from worrying. They didn’t need to. Old and new had been sensitively blended together, and the results were all I’d hoped for and more. “I only wish Mom had lived to see it,” I said, meaning every word.

To be sure, I was surprised by some of what they’d done. How could it have been otherwise? I still remember with perfect clarity the astonishment I felt when I walked into my childhood bedroom for the first time after David stripped it bare:

“Oh, my!” I cried as I gazed through the open door, startled to hear the unfamiliar sound of my voice bouncing off the freshly painted walls. I stepped inside and was no less startled by how small the room looked. Could I really have grown up in this cramped chamber? Was this the place in which I dreamed my youthful dreams of glory? It was–or, rather, it had been. Now it was an empty, memory-free space waiting to be brought to life once more.

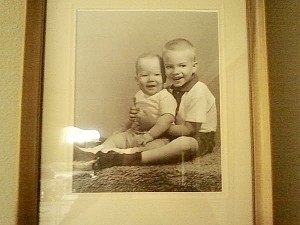

But three years later, that empty space has been turned into a comfy, inviting guest room full of the furniture that used to fill my parents’ bedroom—completely redecorated, yet still as familiar and alive as the face I see in the mirror when I shave each morning. One of the pictures that now hangs on the walls is a studio portrait of my brother and me that was taken when we were very young. It is my favorite image of the two of us. Another is a snapshot of Mrs. T and me at our wedding breakfast, glowing as though we were lit from within by love. Memories crowded in on me as I looked around the room, and I half expected to hear somebody say “This play is called Our Town” when I finally switched off the light and went to sleep.

But three years later, that empty space has been turned into a comfy, inviting guest room full of the furniture that used to fill my parents’ bedroom—completely redecorated, yet still as familiar and alive as the face I see in the mirror when I shave each morning. One of the pictures that now hangs on the walls is a studio portrait of my brother and me that was taken when we were very young. It is my favorite image of the two of us. Another is a snapshot of Mrs. T and me at our wedding breakfast, glowing as though we were lit from within by love. Memories crowded in on me as I looked around the room, and I half expected to hear somebody say “This play is called Our Town” when I finally switched off the light and went to sleep.

* * *

We shopped on Friday and cooked on Saturday morning, and our relatives started ringing the doorbell at the appointed hour, not long after all was in readiness. Unlike me, my cousins and their offspring didn’t fall far from the family tree. They mostly live in Arkansas, Kentucky, Missouri, and Tennessee, close enough to drive to Smalltown in the morning and return home by bedtime, which was what they did. I hadn’t seen any of them since my mother’s funeral, and my heart leaped with joy as they streamed through the door, smiling and excited.

The last straggler showed up just before lunchtime, and we all assembled in the dining room. Uncle Albert, the last of my mother’s surviving siblings and the octogenarian patriarch of the Crosnos, led us in prayer, as he always does when we eat together. (Like most of the family, he is a lifelong churchgoer and an unswerving believer in what the song calls “that old-time religion.”) Then we lined up in the kitchen, piled our paper plates high, found seats at one of the four tables that had been laid throughout the house, and started eating—and talking.

The fare was pretty much what you’d expect to encounter at a family dinner in southeast Missouri: hamburgers, hot dogs, sliced pork loin smoked by my brother, two kinds of potato salad, homemade baked beans, Campbell’s Classic Green Bean Casserole, cheese grits, two relish trays, and a half-dozen different desserts. It was simple and good, and there wasn’t much left when we’d eaten our fill.

The talk was as straightforward as the food, and I doubt that it would be of any particular interest to outsiders. Much of it was couched in a kind of shorthand, the common tongue of people who have known one another all their lives and so don’t need to explain anything in detail save for the sheer pleasure of doing so. Nobody mentioned what they were reading or what movies they’d seen lately. Instead, ancient anecdotes were retold for the umpteenth time as though they were freshly coined, while past travels and present illnesses were described with identical zest.

The talk was as straightforward as the food, and I doubt that it would be of any particular interest to outsiders. Much of it was couched in a kind of shorthand, the common tongue of people who have known one another all their lives and so don’t need to explain anything in detail save for the sheer pleasure of doing so. Nobody mentioned what they were reading or what movies they’d seen lately. Instead, ancient anecdotes were retold for the umpteenth time as though they were freshly coined, while past travels and present illnesses were described with identical zest.

I found such idle chat dull when I was a boy, for I hadn’t lived long enough to understand it, much less appreciate it. Then, a few years later, I read The Edge of Sadness, Edwin O’Connor’s 1962 novel about an alcoholic priest from Boston, in which he describes the table talk of a family of first- and second-generation Irish-American immigrants, and I grasped for the first time the significance of the tales that my relatives told one another at family gatherings:

The conversation continued for some moments in much the same way, and as I listened to it, with amusement and delight and nostalgia, it was so familiar to me that it almost seemed as if I’d never been away from it—and this in spite of the fact that I hadn’t heard it for years now. But it was the same talk with which I had grown up, the talk that belonged, really, to another era and that now must have been close to disappearing, the talk of old men and old women for whom the simple business of talking had always been the one great recreation….And I had listened, drifting along with the tide of words, and as I did the feeling of familiarity grew and grew, the sense of being once more at home in a place I knew.

That’s what it was like for me to sit and eat and listen to my relatives last Saturday afternoon. I luxuriated in the warm and gentle tide of well-worn words, feeling as though I’d found my way back after years of wandering in the wilderness.

After lunch my brother brought a small TV into the family room, and one of my cousins plugged in a video camera and used it to play back a reel of silent home movies from the Fifties and early Sixties that he’d transferred to videotape. The flickering footage, an unbroken succession of Christmases and Easters and birthday parties, was no more eventful than the table talk, but it didn’t matter: we all crowded eagerly round the set, transfixed by the sight of ourselves when young.

After lunch my brother brought a small TV into the family room, and one of my cousins plugged in a video camera and used it to play back a reel of silent home movies from the Fifties and early Sixties that he’d transferred to videotape. The flickering footage, an unbroken succession of Christmases and Easters and birthday parties, was no more eventful than the table talk, but it didn’t matter: we all crowded eagerly round the set, transfixed by the sight of ourselves when young.

Come six o’clock everyone decided simultaneously that it was time to hit the road. It took us a good twenty minutes to say our collective goodbyes. Hands were shaken, hugs exchanged, and the phrase “Let’s do this again real soon” was spoken repeatedly and with self-evident sincerity. At length our twenty-nine guests went their various ways, leaving David, Kathy, and me to clean up the debris, take the extra leaves out of the tables, stash the leftovers in the refrigerator, and congratulate ourselves on a job well done.

* * *

I used to think that mine was an ordinary family. As the Stage Manager in Our Town says of Grover’s Corners, “Nice town, y’know what I mean? Nobody very remarkable ever come out of it, s’far as we know.” More and more, though, I find myself wondering just how ordinary it is to be so nice. It’s the dysfunctional families, after all, that get the ink these days, and it looks as though they’ve become the norm in postmodern America—though possibly not. Either way, I know how lucky I was to be born a Crosno. To come from such unfancy people, ordinary though they may be by the standards of the gilded city in which I now live, is to have a leg up in the long race of life, all the way from the starting gun to the finish line.

I used to think that mine was an ordinary family. As the Stage Manager in Our Town says of Grover’s Corners, “Nice town, y’know what I mean? Nobody very remarkable ever come out of it, s’far as we know.” More and more, though, I find myself wondering just how ordinary it is to be so nice. It’s the dysfunctional families, after all, that get the ink these days, and it looks as though they’ve become the norm in postmodern America—though possibly not. Either way, I know how lucky I was to be born a Crosno. To come from such unfancy people, ordinary though they may be by the standards of the gilded city in which I now live, is to have a leg up in the long race of life, all the way from the starting gun to the finish line.

Mrs. T is under the weather and was unable to accompany me to Smalltown. That being the case, I made a point of taking snapshots at frequent intervals throughout the day and posting them on Twitter and Facebook so that she wouldn’t feel left out of the fun. Late in the afternoon I slipped into my bedroom, logged on to post another picture, and found an e-mail from a longtime New Yorker who was born into a family that is…well, not nearly so close as the Crosnos. “That’s all so beautiful, the pictures and the feeling in them,” it said. “I wish I were in your family.”

* * *

The Band performs Robbie Robertson’s “Rockin’ Chair” at a 1970 concert in Calgary: