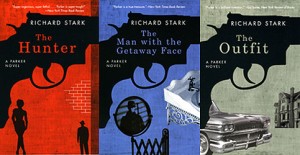

I am, as regular readers of this blog need no reminding, an ardent admirer of the novels of “Richard Stark,” the pseudonym that the late Donald E. Westlake used when writing about Parker, a career criminal of all-too-believable heartlessness. I had the privilege a few years ago of writing an introduction to the University of Chicago’s uniform-edition reprints of Flashfire and Firebreak, two of the very best Parker novels, and I speculated therein on their popularity, which is in certain ways a puzzlement:

I am, as regular readers of this blog need no reminding, an ardent admirer of the novels of “Richard Stark,” the pseudonym that the late Donald E. Westlake used when writing about Parker, a career criminal of all-too-believable heartlessness. I had the privilege a few years ago of writing an introduction to the University of Chicago’s uniform-edition reprints of Flashfire and Firebreak, two of the very best Parker novels, and I speculated therein on their popularity, which is in certain ways a puzzlement:

Anyone who doubts the existence of original sin would do well to reflect on the popularity of these unsettling books, whose “hero,” lest we forget, is a hard-eyed monster of self-will, the kind of guy you don’t want to meet anywhere near a dark alley. Parker’s only virtues are his intelligence and his professionalism—but somehow you always end up rooting for him. Nietzsche knew why: when you look into an abyss, the abyss looks into you. When I first started reading about Parker, I thought of the words of Dostoevsky’s Ivan Karamazov: “If you were to destroy in humanity the belief in its immortality, not only love but every vital force for the continuation of earthly life would at once dry up. Moreover, then nothing would be immoral any more, everything would be permitted, even cannibalism.” Up to a point, that applies to Parker, a man to whom nothing but amateurishness is immoral. Even more to the point, though, is Liliana Cavani’s 2002 film version of Ripley’s Game, in which these words are put into the mouth of Tom Ripley, Patricia Highsmith’s anti-hero: “I lack your conscience and when I was young that troubled me. It no longer does. I don’t worry about being caught because I don’t believe anyone is watching.”

Like Ripley, who is a real sociopath, Parker has no conscience. Somehow, though, I doubt that has ever troubled him. I think he got up one morning, decided for reasons known only to himself that no one was watching except for the cops, and decided to act accordingly. Nor do I think there was anything dramatic about his decision, no Farewell remorse…evil be thou my good moment to stun the groundlings. And that’s what makes Parker so interesting, so seductive, and so wholly unlike most of the rest of us: he just doesn’t care, and never did.

All this is true as far as it goes, but I’m not sure that it goes far enough. Parker is, after all, a brute by any conceivable standard of conduct, in addition to which he is portrayed by Stark as a creature so cold as to be, at least in theory, utterly unsympathetic. Why, then, do we—do I—wish him well? For we do: about that there can be no doubt. We want him to prevail in his capers, no matter the cost in human life. I know, they’re only novels, but so what? Real or not, Parker is a bad man. What, then, makes him so attractive?

Part of the answer may have to do with the fact that I am not infrequently drawn to the Parker novels at times when my own life is more chaotic than usual. While I’m not obsessive about much of anything, I do prize order—I’m a native-born list-maker—and I don’t much care to be reminded that I actually have very little control over the world and my place in it. Neither does Parker, but unlike the rest of us, he’s prepared to do something about it, up to and including murder. Surely that is the ultimate source of his appeal: he does as he pleases, and gets away with it. Moreover, he does it in the name of order—his order. The world exists to satisfy his wants, which he pursues in a manner so disciplined that it is all but impossible not to admire, however backhandedly.

Part of the answer may have to do with the fact that I am not infrequently drawn to the Parker novels at times when my own life is more chaotic than usual. While I’m not obsessive about much of anything, I do prize order—I’m a native-born list-maker—and I don’t much care to be reminded that I actually have very little control over the world and my place in it. Neither does Parker, but unlike the rest of us, he’s prepared to do something about it, up to and including murder. Surely that is the ultimate source of his appeal: he does as he pleases, and gets away with it. Moreover, he does it in the name of order—his order. The world exists to satisfy his wants, which he pursues in a manner so disciplined that it is all but impossible not to admire, however backhandedly.

Backflash, another of the Parker novels that I like best, contains this illuminating paragraph:

So the question is, why not gamble? Parker’d never thought about it, he just knew it was pointless and uninteresting. He said, “Turn myself over to random events? Why? The point is to control events, and they’ll still get away from you anyway. Why make things worse? Jump out a window, see if a mattress truck goes by. Why? Only if the room’s on fire.”

I don’t gamble, either, and when I first read that passage, I smiled at the sound of a kindred spirit. Nor did I cross myself hastily and whisper, No, no, just kidding, I’m not that kind of guy! To be sure, I’m not that kind of guy, or anything remotely like him, but I know very well that there is a part of me, however small, that is tempted to adopt Parker’s absolutism as a mode of life. Indeed, there can’t be many of us who don’t feel that temptation on a fairly regular basis, never more than when the dam that is our daily life suddenly starts springing multiple leaks. When things go wrong for Parker, by contrast, he knows exactly what to do: he shoots people until they go right again. He likes things neat.

Such neatness, needless to say, is an idle fantasy. Sooner or later everybody’s dam starts springing leaks, and in time it breaks wide open and washes us away. But it’s peculiarly soothing to imagine the existence of a man who adamantly refuses to turn himself over to random events, whatever they may be, and it goes down even more smoothly when you find yourself in the waiting room of an intensive-care unit, or midway through a sleepless night. Maybe that’s what fantasy is all about.