One advantage of middle age (yes, it has them) is that you’re still young enough to embrace new technologies, but old enough not to take them for granted. That’s how I feel about my iPod Classic, a replacement for the original iPod that I bought in 2004, three years after the device went on the market. Of all the shiny new gadgets that have entered my life during the past quarter-century, it is the one that has given me the most pleasure.

When I went off to college forty-one years ago, I carted along my record collection, crammed into a four-foot-long metal traveling case that my father built for me in his basement workshop. My iPod now contains many times more music than did that cumbersome box, all of it packed neatly onto a hard drive small enough to slip into my shirt pocket. At present it holds 5,372 “songs” ranging in length from Ned Rorem’s “O You Whom I Often and Silently Come” (twenty-seven seconds) to Willem Mengelberg’s 1928 recording of Tchaikovsky’s Fifth Symphony with the Concertgebouw Orchestra (forty-four minutes). In between can be found examples of every possible kind of music: Bach and the Bad Plus, Fred Astaire and T-Bone Walker, Hank Williams and the Dixieaires, Steely Dan and Lana Del Rey.

When I went off to college forty-one years ago, I carted along my record collection, crammed into a four-foot-long metal traveling case that my father built for me in his basement workshop. My iPod now contains many times more music than did that cumbersome box, all of it packed neatly onto a hard drive small enough to slip into my shirt pocket. At present it holds 5,372 “songs” ranging in length from Ned Rorem’s “O You Whom I Often and Silently Come” (twenty-seven seconds) to Willem Mengelberg’s 1928 recording of Tchaikovsky’s Fifth Symphony with the Concertgebouw Orchestra (forty-four minutes). In between can be found examples of every possible kind of music: Bach and the Bad Plus, Fred Astaire and T-Bone Walker, Hank Williams and the Dixieaires, Steely Dan and Lana Del Rey.

Thanks to my iPod, I carry the whole history of music with me wherever I go, and can listen to any part of it whenever I choose. If I wish, I can push a button and hear Sergei Rachmaninoff playing his Paganini Rhapsody, or listen to a 1908 performance of “Unto Brigg Fair” by Joseph Taylor, the English folksinger from whom Percy Grainger collected that song three years earlier. Having launched my writing career on a manual typewriter, I continue to find no difficulty whatsover in marveling at the mere existence of the ingenious little device that allows me to do so.

The ubiquity of recorded music has been much lamented by any number of wise men. I understand and appreciate their reservations, which Benjamin Britten summed up eloquently in 1964:

One must face the fact today that the vast majority of musical performances take place as far away from the original as it is possible to imagine: I do not mean simply Falstaff being given in Tokyo, or the Mozart Requiem in Madras. I mean of course that such works can be audible in any corner of the globe, at any moment of the day or night, through a loudspeaker, without question of suitability or comprehensibility. Anyone, anywhere, at any time, can listen to the B minor Mass upon one condition only—that they possess a machine. No qualification is required of any sort—faith, virtue, education, experience, age. Music is now free for all. If I say the loudspeaker is the principal enemy of music, I don’t mean that I am not grateful to it as a means of education or study, or as an evoker of memories. But it is not part of true musical experience. Regarded as such it is simply a substitute, and dangerous because deluding. Music demands more from a listener than simply the possessions of a tape-machine or a transistor radio. It demands some preparation, some effort, a journey to a special place, saving up for a ticket, some homework on the program perhaps, some clarification of the ears and sharpening of the instincts. It demands as much effort on the listener’s part as the other two corners of the triangle, this holy triangle of composer, performer and listener.

In truth, I think Britten was mostly right. Among other unfortunate things, the ubiquity of recorded music has largely killed off the amateur back-porch music-making that was one of the joys of my youth. But that was well on the way to happening long before the invention of the laptop computer and its offshoots. And if we are more passive listeners today, then we also have access to an infinitely wider and more varied range of listening possibilities than we did when I was young.

In any case, it doesn’t really matter whether he was right: the deed is done, and only a self-consciously curmudgeonly fool would bemoan the results. To borrow a line from V.S. Naipaul, the world is what it is. Far better, then, to seize what it offers and make the most of it—and that, for me, includes the iPod. Two days ago I downloaded a recording of Dmitri Shostakovich’s Piano Quintet that was made by Shostakovich and the Beethoven Quartet in Moscow in 1940, one month after they gave the premiere of that masterpiece. Do I regret being able to do so? Not in the slightest—any more than I regret being able to go to YouTube and watch videos of Britten performing his own music.

It was with much bemusement that I learned last year that Apple had finally stopped manufacturing the iPod Classic. It is now officially obsolete, superseded by iPads and smartphones and various other shiny do-it-all gadgets, none of which I own. I continue instead to rely on my trusty iPod, my increasingly dilapidated MacBook, and my positively ancient flip phone, and for the present I see no compelling reason to replace any of them. Sooner or later, of course, I’ll discard them all and lurch into a new technological age, though not quite yet, life being complicated enough as is. But when I do, I hope that I continue to feel some sliver of the shivery thrill that I felt the first time I downloaded a song from iTunes. One should never get used to miracles.

It was with much bemusement that I learned last year that Apple had finally stopped manufacturing the iPod Classic. It is now officially obsolete, superseded by iPads and smartphones and various other shiny do-it-all gadgets, none of which I own. I continue instead to rely on my trusty iPod, my increasingly dilapidated MacBook, and my positively ancient flip phone, and for the present I see no compelling reason to replace any of them. Sooner or later, of course, I’ll discard them all and lurch into a new technological age, though not quite yet, life being complicated enough as is. But when I do, I hope that I continue to feel some sliver of the shivery thrill that I felt the first time I downloaded a song from iTunes. One should never get used to miracles.

* * *

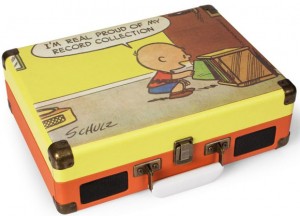

Here is the Peanuts strip from which the above panel was adapted for commercial use. It was originally published in 1952.

Peter Pears and Benjamin Britten perform Britten’s arrangement of “O Waly Waly.” This performance was taped in front of an audience at the BBC’s Riverside Studios in 1964: