In today’s Wall Street Journal I review a related pair of musicals, the premiere of Hamilton and a Florida revival of West Side Story. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

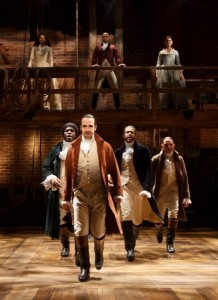

“Hamilton,” Lin-Manuel Miranda’s hip-hop chronicle of the rise and fall of the man on the $10 bill, is the most exciting and significant musical of the past decade. Even though it’s an 18th-century costume drama, “Hamilton” sounds as up to date as a Nicki Minaj single. Nor is its surging immediacy merely a function of Mr. Miranda’s decision to tell Alexander Hamilton’s story in the blunt language of rap, for “Hamilton” is as theatrically vital as it is musically fresh. Yes, it’s been staged with down-and-dirty flair, and Thomas Kail and Andy Blankenbuehler, the director and choreographer, are at least as responsible for its effectiveness as is Mr. Miranda. Nevertheless, this is Mr. Miranda’s show—not only did he write the words and music, but he plays Hamilton—and so he deserves the bulk of the credit for its success. And if you’re wondering whether a multiracial musical about one of the founding fathers could possibly amount to anything more than a knee-jerk piece of progressive sermonizing, get ready for the biggest surprise of all, which is that this show is at bottom as optimistic about America as “1776.” American exceptionalism meets hip-hop: That’s “Hamilton.”

To be sure, “Hamilton” does have an ideological message, which is that America should take pride in its immigrant heritage. Ours, after all, is a land in which it was possible for a low-born bastard from the West Indies to become George Washington’s right-hand man, a point that Mr. Miranda makes clear right from the start: “Another immigrant, comin’ up from the bottom/His enemies destroyed his rep, America forgot him.” “Hamilton” is, in other words, an apologia for its hero, who in Mr. Miranda’s opinion has never received his due at the bar of history….

To be sure, “Hamilton” does have an ideological message, which is that America should take pride in its immigrant heritage. Ours, after all, is a land in which it was possible for a low-born bastard from the West Indies to become George Washington’s right-hand man, a point that Mr. Miranda makes clear right from the start: “Another immigrant, comin’ up from the bottom/His enemies destroyed his rep, America forgot him.” “Hamilton” is, in other words, an apologia for its hero, who in Mr. Miranda’s opinion has never received his due at the bar of history….

Structurally speaking, “Hamilton” is a pageant that unfolds in a procession of dramatic tableaux. But unlike Bertolt Brecht, whose “Life of Galileo” is its dramaturgical model, Mr. Miranda is not much interested in Hamilton’s ideas, which he praises without describing (he disposes of “The Federalist” in two hasty paragraphs). What he cares about is Hamilton the personality, whom he portrays as a quintessential striver, by turns bumptious, arrogant and unsure, driven to excel by the gnawing suspicion that his time may be short: “How do you write like tomorrow won’t arrive?/How do you write like you need it to survive?”

“Hamilton” is also a story of political intrigue, so much so that in “The Room Where It Happens,” the biggest and best production number, Aaron Burr (Leslie Odom, Jr.) walks us through the fine art of compromise: “No one really knows how the parties get to yes/The pieces that are sacrificed in ev’ry game of chess.” Here it resembles Steven Spielberg’s “Lincoln,” an equally talky historical pageant that makes high drama out of backroom wheeling and dealing. But the “talk” in “Hamilton” consists of rhymed couplets set to a ceaseless stream of propulsively danceable music, and just as Mr. Miranda invites us to take for granted a stageful of non-white founding fathers dressed in drawing-room garb, so does he pull off the near-magical feat of telling his story in hip-hop style simply by going ahead and doing it….

What “Hamilton” is to 2015, “West Side Story” was to 1957, a musical that was as much a part of its historical moment as a tabloid headline. So it was a near-miraculous coincidence that I happened to see a Florida revival of Leonard Bernstein’s Broadway opera about a Manhattan gang war the night after “Hamilton” opened in New York. The two shows have much in common—among other things, they’re both parables of the problem of assimilation—and Riverside Theatre’s well-sung and unusually well-danced production of “West Side Story,” directed by DJ Salisbury, is a solid, meritorious piece of work….

According to the program, Alex Sanchez’s choreography is “based on the original by Jerome Robbins,” and it incorporates all of the master’s signature moves to soaring effect. The sets and costumes are conventional but pleasing, and the orchestra is as good as a 10-piece band can hope to be (the original Broadway production had 28 players in the pit).

As for the show itself, Arthur Laurents’ book, with its clunky made-up teenage slang, hasn’t aged well, but Bernstein’s score is as potent as ever, a timeless testament to the power of song to stir the heart….

* * *

To read my full review of Hamilton, go here.

To read my full review of West Side Story, go here.

The trailer for Hamilton: