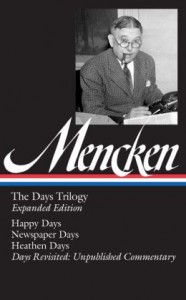

The Library of America is about to bring out an omnibus edition of Happy Days, Newspaper Days, and Heathen Days, in which H.L. Mencken collected the reminiscential essays that he published in The New Yorker in the Thirties and Forties.

The Library of America is about to bring out an omnibus edition of Happy Days, Newspaper Days, and Heathen Days, in which H.L. Mencken collected the reminiscential essays that he published in The New Yorker in the Thirties and Forties.

National Review recently asked me to write about this volume. It happened that I hadn’t looked at any of the Days books since The Skeptic, my Mencken biography, was published in 2002. Nor had I looked at The Skeptic since I last wrote about Mencken. That was four years ago, in a New Criterion essay about the Library of America’s two-volume collection of his Prejudices essays in which I suggested that

Mencken might possibly be a young person’s writer, one who excites the unfinished mind but has less to offer those who have seen more of life. Certainly those who look to literature for a portrait of the human animal that is rich in chiaroscuro will not find it in the Prejudices….If a great essayist is one who succeeds in getting his personality onto the page, then H.L. Mencken qualifies in spades. The problem is that his personality grows more predictable with closer acquaintance, just as the tricks of his prose style grow more familiar. Like most journalists, he is best consumed not in the bulk of a twelve-hundred-page boxed set but in small and carefully chosen doses.

Hence it was a very pleasant surprise to return to the Days books after a long absence and find my original judgment on them to be confirmed anew. I described Happy Days as “one of [Mencken]’s most completely realized achievements…a masterpiece of pure style” in The Skeptic, and went on to say that Newspaper Days was “at least as good….It, too, is a not-so-minor masterpiece of affectionate reminiscence, one that in a better-regulated world would be recognized as a modern classic.”

The operative word here is “style.” As I said in the epilogue of The Skeptic, Mencken’s enduring strength as a writer “is less a function of his particular convictions than of the firmly balanced prose rhythms and vigorous diction in which they are couched. It is, in short, a triumph of style.” It was in the Days books that his style reached a peak of perfection, and as I reread Happy Days I was struck all over again by how its pages are festooned with utterly characteristic phrases through which his personality shines forth.

The operative word here is “style.” As I said in the epilogue of The Skeptic, Mencken’s enduring strength as a writer “is less a function of his particular convictions than of the firmly balanced prose rhythms and vigorous diction in which they are couched. It is, in short, a triumph of style.” It was in the Days books that his style reached a peak of perfection, and as I reread Happy Days I was struck all over again by how its pages are festooned with utterly characteristic phrases through which his personality shines forth.

Here are some of my favorites:

• “There is a photograph of me at eighteen months which looks like the pictures the milk companies print in the rotogravure sections of the Sunday papers, whooping up the zeal of their cows. If cannibalism had not been abolished in Maryland some years before my birth I’d have butchered beautifully.”

• “To this day I can’t tie a bow tie, though I have taken lessons over and over again from eminent masters…This inapacity for minor dexterities has pursued me all my life, often to my considerable embarrassment.”

• “She had a fist like a pig’s foot and was not above clouting any boy who annoyed her.”

• On a teacher whose spankings were ineffective: “He rattaned conscientiously, but without any noticeable style.”

• On the hot dogs sold in turn-of-the-century Baltimore: “They contained precisely the same rubbery, indigestible pseudo-sausages that millions of Americans now eat, and they leaked the same flabby, puerile mustard.”

• “The Baltimoreans of those days were complacent beyond the ordinary, and agreed with their envious visitors that life in their town was swell.”

• “The Baltimoreans of those days were complacent beyond the ordinary, and agreed with their envious visitors that life in their town was swell.”

• “The impact of such lovely country upon a city boy barely eight years old was really stupendous. Nothing in this life has ever given me a more thrilling series of surprises and felicities.”

• “To this day I can taste it at the moments when an aging man’s memory searches through his lost youth for bursts of complete felicity.”

I wish I’d quoted that one in The Skeptic, since it is a perfect summary of what Happy Days is all about. And though I’ve never wanted to be able to write like Mencken—to be influenced by him is by definition to imitate him, which is a dead end—I hope that every once in a while my own writing recalls, however vaguely, his matchless verbal vividness.