The Wall Street Journal has given me an extra drama column in today’s paper in which to comment on John Lithgow’s King Lear in New York’s Central Park. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

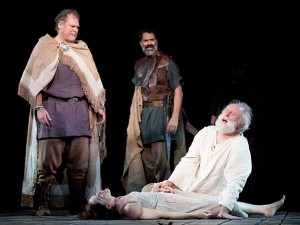

How is it that “King Lear,” Shakespeare’s darkest and most challenging drama, has lately become almost popular in a fundamentally optimistic country like America? I’ve seen 13 “Lears” in the past decade, and the floodtide of interest in the plight of the mad old king and his murderously ungrateful daughters shows no signs of slackening. The most persuasive explanation of the play’s vogue is that aging baby boomers on both sides of the proscenium are fascinated by a tragedy that can be plausibly interpreted as hinging on the onrushing senility of its central character. Whatever the reason, the Public Theater is now performing “Lear” in Central Park for the first time since 1973, with a white-bearded John Lithgow—who was born in 1945, at the very start of the boom—in the title role. And while I don’t know anyone who thinks that Mr. Lithgow is a natural Lear, he’s giving a performance so deeply considered and richly realized as to overcome most of the obvious objections to his casting.

Primary among those objections is that save for being unusually tall, Mr. Lithgow is as unregal as an actor can be. He is the quintessential comic WASP, at once haughty and absurd, and he is unfailingly effective in plays in which such folk are brought low, like David Henry Hwang’s “M. Butterfly” or David Auburn’s “The Columnist.” But while “Lear” has its moments of black comedy, its anti-hero is nonetheless heroic: He is pitiful, not preposterous.

Primary among those objections is that save for being unusually tall, Mr. Lithgow is as unregal as an actor can be. He is the quintessential comic WASP, at once haughty and absurd, and he is unfailingly effective in plays in which such folk are brought low, like David Henry Hwang’s “M. Butterfly” or David Auburn’s “The Columnist.” But while “Lear” has its moments of black comedy, its anti-hero is nonetheless heroic: He is pitiful, not preposterous.

As a result, Mr. Lithgow is playing at all times against type—and he gets away with it, filling his space with sharply drawn details that carry the sting of surprise. Never before have I seen a Lear who makes it so clear that he wants to be generous to Cordelia, his good daughter (played by Jessica Collins, who is quietly touching), or who articulates with such exactly graded clarity his descent into madness….

So yes, this is a problematic “Lear.” On the other hand, most “Lears” are problematic—that’s in the nature of the play—and the second half in particular is so charged with passion that it will likely sweep you away, reservations notwithstanding….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.