The MacDowell Colony, to which I retreated two weeks ago, looks like a cross between an old-fashioned summer camp and a charmingly dilapidated country inn. Colony Hall, the rustic but well-kept main building, bears an uncanny resemblance to Storm King Lodge, where Mrs. T and I go without fail each year to cover a nearby theater festival. You’d never guess that this place harbors some thirty-odd artists, all of whom are here not to put their feet up and take it easy but to work–at times quite desperately hard–on projects of their own choosing.

The MacDowell Colony, to which I retreated two weeks ago, looks like a cross between an old-fashioned summer camp and a charmingly dilapidated country inn. Colony Hall, the rustic but well-kept main building, bears an uncanny resemblance to Storm King Lodge, where Mrs. T and I go without fail each year to cover a nearby theater festival. You’d never guess that this place harbors some thirty-odd artists, all of whom are here not to put their feet up and take it easy but to work–at times quite desperately hard–on projects of their own choosing.

Part of what makes MacDowell so unusual is that it is specifically organized to make its residents feel special. The staff goes far out of its way to care for us, and the cooks, if anything, actually go too far. They always serve you more food than you ask for at breakfast, and it’s always so tasty that it takes an act of will not to clean your plate. Because working artists tend not to be valued so highly in what some of my fellow colonists now call “the world,” the experience of being treated with such consideration can be overwhelming. A young poet who came here last week actually burst into tears when she walked through the front door of Colony Hall for the first time.

Best of all is the freedom from the tyranny of the clock that MacDowell confers upon its fortunate guests. In my case, it borders on the astonishing. The days flow by in an undifferentiated stream of voluntary solitude. I have no shows to see and no deadlines to hit. I don’t even make lunch for myself–it’s delivered to my studio in a picnic basket. All I have to do is show up at six-thirty each night for dinner.

Best of all is the freedom from the tyranny of the clock that MacDowell confers upon its fortunate guests. In my case, it borders on the astonishing. The days flow by in an undifferentiated stream of voluntary solitude. I have no shows to see and no deadlines to hit. I don’t even make lunch for myself–it’s delivered to my studio in a picnic basket. All I have to do is show up at six-thirty each night for dinner.

I find it no less liberating that I must walk to the library to check my e-mail and surf the web (there is no wi-fi anywhere else at MacDowell). Since I didn’t bring a car, I rarely leave the grounds, and I’m utterly content to stay put. If, like me, you’ve lived by the clock for the whole of your adult life, this freedom is a boon–though it also enables workaholism, which is, like most blessings, a mixed one.

What keeps me on an even keel is the fact that my fellow colonists are all both nice and interesting, and that I didn’t know any of them before I came here. It helps, too, that I spend most of my evenings in the company of an unusually wide range of artists, which is far more stimulating than hanging out exclusively with, say, playwrights, composers, or–eeuuww–critics. All of us are expected, though not required, to give a presentation of our work at some point during our stay, and I never fail to attend these nighttime events, which so far have been unfailingly satisfying. Needless to say, it can be a scary prospect to stand up in front of a roomful of artists and read a piece of your own writing, but I’ve never spoken to a more attentive or comprehending audience.

Because of all this, MacDowell is an ideal place to make new friends. Not only are you surrounded by fascinating people, but you have as much time as you want to get to know them as well as you wish. To date I’ve become close to four colonists, and I expect to stay in touch with all of them after I return to the world.

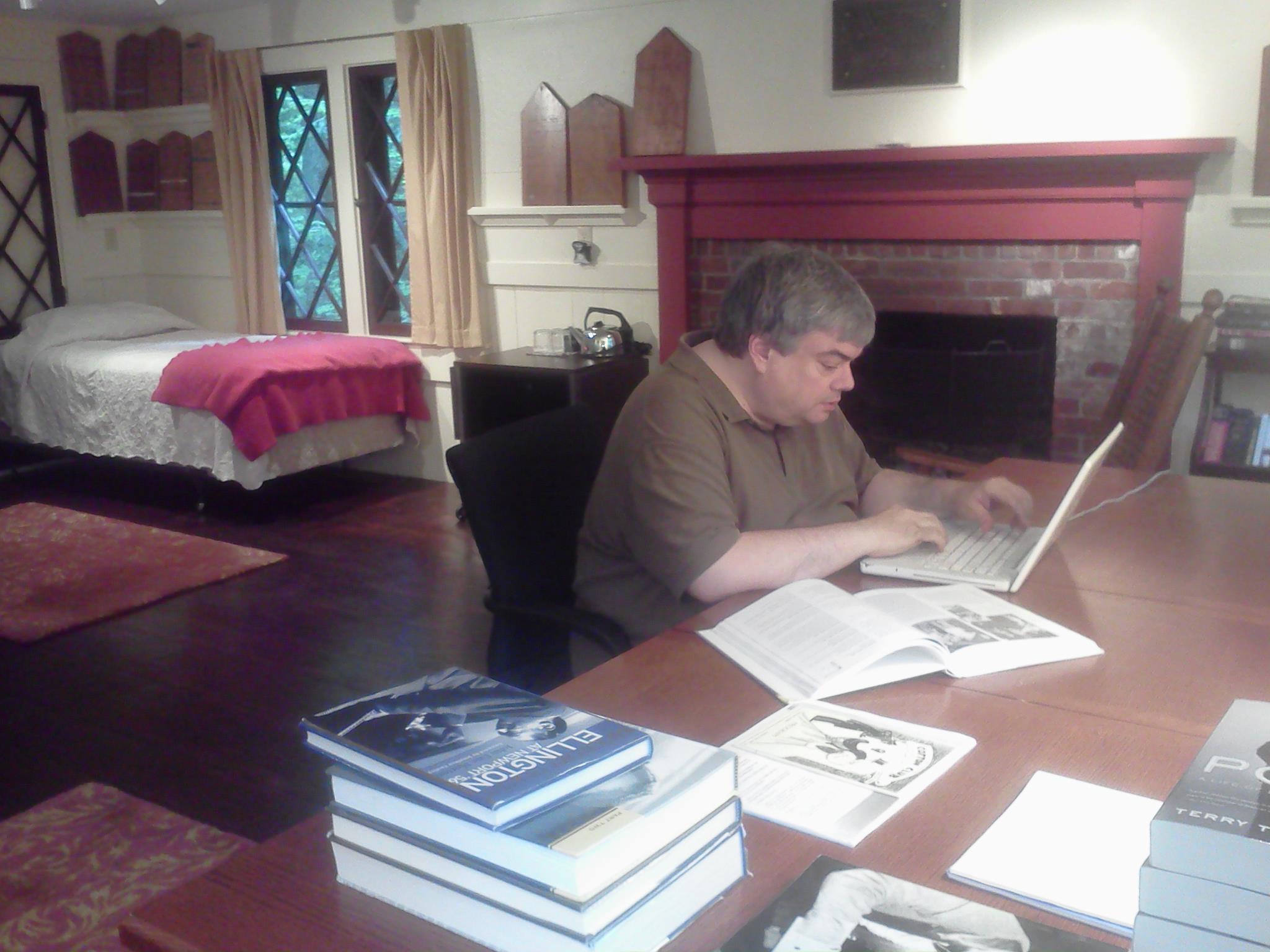

Never before have I presented myself to a group of strangers not as a critic but as an artist. It feels good, but it also means that I have to put my money where my mouth is. After breakfast I spend a half-hour in the stone-walled library, tweeting away frantically before pulling the plug and heading down the path to my studio, accompanied by the sound of twittering birds. At first I feel like a drunk swearing off, but no sooner do I set up my laptop than I get down to business, and when the picnic basket containing my lunch is placed on my stoop four hours later, I marvel at how quickly the time went.

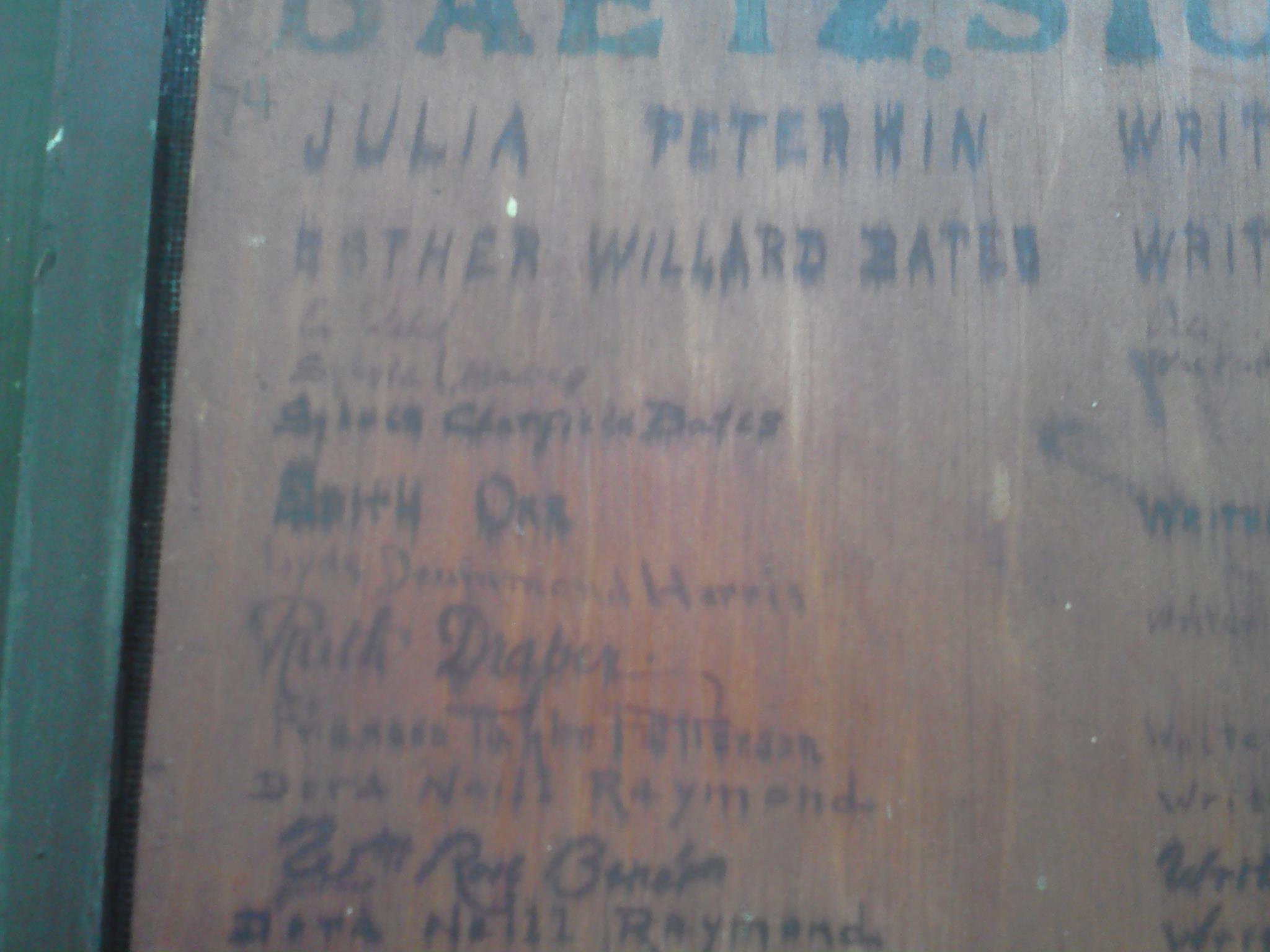

The walls of each MacDowell studio are covered with wooden “tombstones.” At the end of his stay, each colonist inscribes his name on the newest tombstone, and all those who follow him can know who their predecessors were. My studio, Baetz, has previously been occupied by such worthies as James Baldwin, Louise Bogan, Spalding Gray, and Romulus Linney. Also on the walls are an assortment of well-known contemporaries (Lisa Kron, Stephen Karam) and three people whom I know personally, one of whom is a good friend and one of whom…well, isn’t.

The walls of each MacDowell studio are covered with wooden “tombstones.” At the end of his stay, each colonist inscribes his name on the newest tombstone, and all those who follow him can know who their predecessors were. My studio, Baetz, has previously been occupied by such worthies as James Baldwin, Louise Bogan, Spalding Gray, and Romulus Linney. Also on the walls are an assortment of well-known contemporaries (Lisa Kron, Stephen Karam) and three people whom I know personally, one of whom is a good friend and one of whom…well, isn’t.

Some I admire, some I don’t, but most I simply don’t know at all. Hence the tombstones in my studio are mute testimony to the vanity of human wishes, covered as they are with the names of literally hundreds of forgotten and near-forgotten writers. A few of them (Lael Wertenbaker, W.D. Snodgrass) used to be modestly famous but now are known only to pilgrims with unusually retentive memories. It is sobering to think of them seated at the desk where I now sit, trying in vain to write their way into posterity. Indeed, Edward MacDowell himself might well be forgotten were it not for this place.

Some I admire, some I don’t, but most I simply don’t know at all. Hence the tombstones in my studio are mute testimony to the vanity of human wishes, covered as they are with the names of literally hundreds of forgotten and near-forgotten writers. A few of them (Lael Wertenbaker, W.D. Snodgrass) used to be modestly famous but now are known only to pilgrims with unusually retentive memories. It is sobering to think of them seated at the desk where I now sit, trying in vain to write their way into posterity. Indeed, Edward MacDowell himself might well be forgotten were it not for this place.

A few colonists admit to fearing the tombstones, while others are inspired by them. For me it was electrifying to discover that Ruth Draper had occupied my studio in 1929. Will I be as well remembered eighty-three years from now as she is today? Or am I destined to grow as moldy as Enoch Soames? It’s sobering to confront each day a reminder of how long the odds against me really are.

Most of the time, though, I shrug off such night thoughts. I’m here to do my work as well as I can and hope for the best, and I think I’ve been working well. Not at first, though. For the first couple of days my ears were ringing around the clock. Then the hum and buzz of the world faded away, and ever since then I’ve been piling up words. I’ve revised Satchmo at the Waldorf and the libretto of The Letter and written two chapters of Mood Indigo: A Life of Duke Ellington, eaten three dozen excellent meals, relished the company of a like number of delightful people, and spent countless hours walking up and down the wooded paths that run through the grounds.

Most of the time, though, I shrug off such night thoughts. I’m here to do my work as well as I can and hope for the best, and I think I’ve been working well. Not at first, though. For the first couple of days my ears were ringing around the clock. Then the hum and buzz of the world faded away, and ever since then I’ve been piling up words. I’ve revised Satchmo at the Waldorf and the libretto of The Letter and written two chapters of Mood Indigo: A Life of Duke Ellington, eaten three dozen excellent meals, relished the company of a like number of delightful people, and spent countless hours walking up and down the wooded paths that run through the grounds.

Between Colony Hall and my studio is a tree-lined meadow that fills up with fireflies most every night. When I first saw it two weeks ago, I wondered if it was a piece of installation art. Now I know better. What it is–like the rest of the MacDowell Colony–is magic.