For those who asked, you can now read all three parts of “The Long Goodbye” in a single file by clicking on the link.

* * *

Sooner or later, the approach of death imposes an iron economy of illusion. The euphemisms that once sustained you start to cloy, and at length a time comes when you can no longer bear to speak or hear them. I saw it happen to a friend of mine who was dying by inches of a degenerative disease. One day he told me that he could no longer stand the company of optimists who urged him to “think positive.” He knew he was dying and that the end would be terrible, and his only comfort, such as it was, came from being able to talk about it honestly with those of his friends who were willing to hear him do so. Not many were.

Sooner or later, the approach of death imposes an iron economy of illusion. The euphemisms that once sustained you start to cloy, and at length a time comes when you can no longer bear to speak or hear them. I saw it happen to a friend of mine who was dying by inches of a degenerative disease. One day he told me that he could no longer stand the company of optimists who urged him to “think positive.” He knew he was dying and that the end would be terrible, and his only comfort, such as it was, came from being able to talk about it honestly with those of his friends who were willing to hear him do so. Not many were.

I remembered that conversation when the bottom fell out of my mother’s life last December. She, too, was dying by inches, but none of us, including her, had been ready to face the truth until she was assaulted by pain of the most savage and unrelenting kind, an agony to which all normal remedies were unequal. Then, on the night after Christmas, she looked at me and said, matter-of-factly, “I think I’m going to die.”

I replied, half stupidly and half practically, “Do you mean eventually, or now?”

“Now,” she said.

It was no time for gentle evasions. I promised that we’d do our best to take care of her and make what was to come as easy as we could. Then I stepped into the corridor, called my brother on his cellphone, and repeated to him, word for word, what she had said. He rushed to the nursing home, and within the hour a hospice-care representative met with us in my mother’s room. The talk was simple and straightforward. Not long after that, she was given a dose of morphine strong enough to soothe her pain, and the only question that remained was the simplest one of all: how much longer would she live?

What is true for the dying turns out to be no less true for those who love them. Set aside the language of hope and you soon start speaking in another tongue, one that is frank enough to horrify innocent outsiders who don’t know what it’s like to watch a parent die. I loved my mother no less after I accepted the awful fact of her coming death, but I also caught myself saying things out loud that not so long before I wouldn’t have allowed myself even to think. First came It’s time, then She’d be better off dead, and eventually If she dies tomorrow, I won’t have to reschedule our flight to California.

It was crass and callous and I hated myself for it, above all because I knew that it was nothing more than the plain truth.

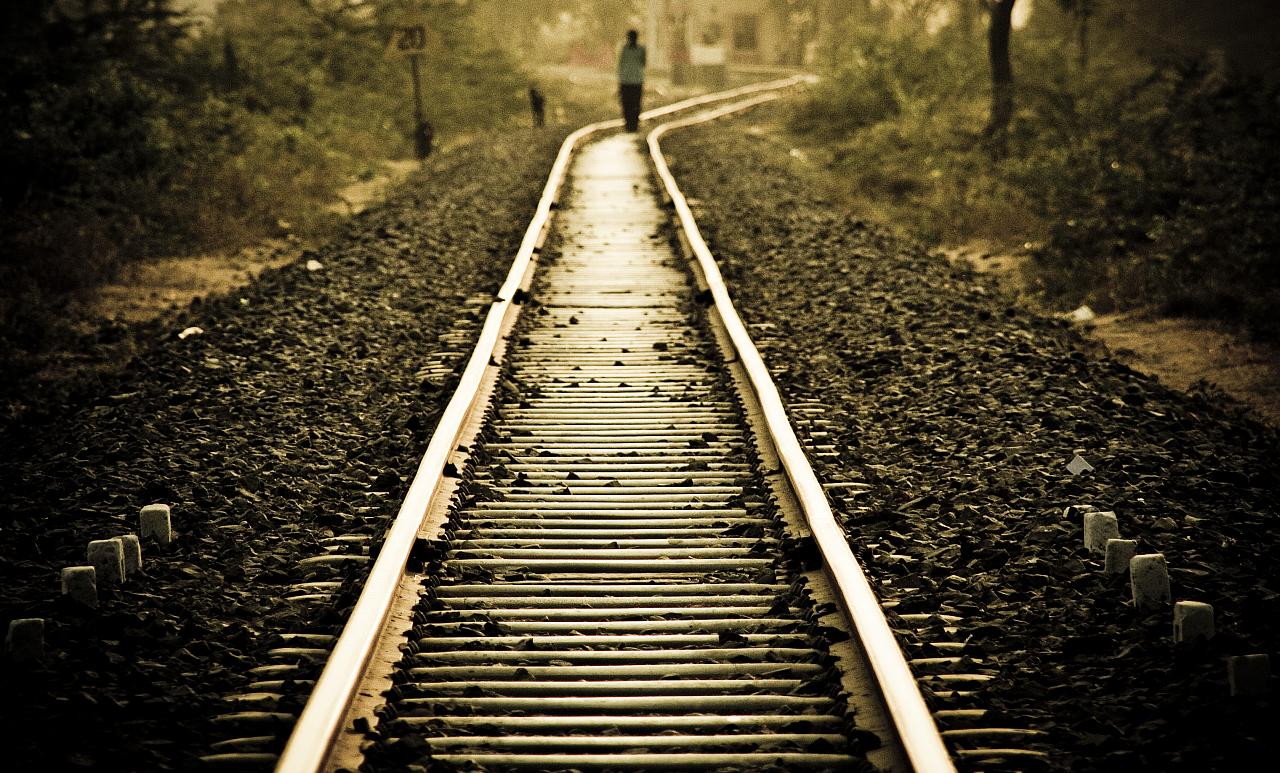

Try as you will, you can’t ignore the daily necessities. As W.H. Auden wrote of human suffering in Musée des Beaux Arts, “It takes place/While someone else is eating or opening a window or just walking dully along.” Barely an hour after my father died, I took my mother to a Burger King around the corner from the hospital, where we ordered Whoppers and chatted lovingly about his quirks and foibles. He was dead, after all, and we hadn’t eaten the whole day long. It would no more have profited my father for us to starve ourselves than it would have profited my mother for me to forget that when the funeral is over, the mourners must go back to work sooner or later–usually sooner.

Try as you will, you can’t ignore the daily necessities. As W.H. Auden wrote of human suffering in Musée des Beaux Arts, “It takes place/While someone else is eating or opening a window or just walking dully along.” Barely an hour after my father died, I took my mother to a Burger King around the corner from the hospital, where we ordered Whoppers and chatted lovingly about his quirks and foibles. He was dead, after all, and we hadn’t eaten the whole day long. It would no more have profited my father for us to starve ourselves than it would have profited my mother for me to forget that when the funeral is over, the mourners must go back to work sooner or later–usually sooner.

* * *

From the end of December, when I returned to New York, to the beginning of May, not a day went by without my thinking of my mother’s death. At first I thought about it constantly, taking for granted that it would happen in a matter of weeks and–yes–at what I assumed would be an impossibly inconvenient moment for me. (Shame! shame! I told myself, unable to repress the selfish thought and unwilling to acknowledge, much less accept, that everyone thinks such unworthy things at one time or another.) But she didn’t die, and I got used to the idea that she might cling to life for an unknowable amount of time, and that every day she stayed alive would be a day of suffering, not only for her but for all those who knew her best and loved her most. Dostoevsky said it: “Man gets used to everything–the beast!”

Having long been in the habit of calling my mother every night or two from wherever I happened to be, I now found myself conducting one-sided phone “conversations” in which she whispered the feeblest of greetings, then listened in silence while I rattled on at length about what I’d done that day, trying in vain to distract her. She was too weak to say anything more than hello, or even to grasp the receiver in her hand. Instead my brother stood at her bedside and held it to her ear, assuring me afterward that he could tell from the look in her eyes that she was glad to hear my voice.

In March I carved four days out of my schedule and flew to Smalltown. I knew that the last month of the Broadway season would be unusually crowded with opening nights, and feared that if I didn’t see my mother at once, I might not be able to get back again until the final crisis. By then, though, I had grown accustomed to the notion that she might linger indefinitely. It never occurred to me that she would have deteriorated so much in the preceding three months that the sight of her would stun me. I had to exert the utmost self-control to keep my knees from buckling when I first saw her lying in bed, ashen and wasted. (“I didn’t try to warn you because I figured it wouldn’t help,” my ever-sensible brother told me later that night. “Nothing could have prepared you for the way she looks now.”)

“I’m here, Mom,” I said, trying to sound unshaken. “I told you I was coming, and now I’m here.”

She looked up and asked, “Is it really you?” It was the first full sentence that she’d spoken to me in a month.

“It’s me. And I love you.”

“How much?”

I stretched my hands as far apart as I could. “This much,” I said, and she smiled one last time at the ritual that had sprung up between us not long after she went into the nursing home the preceding summer.

No matter how ill she might be, my mother had always been able to pull herself together whenever I came to see her. For a few minutes it almost seemed as if she might still have the power to draw back from the brink of death. But such energy as she was able to muster soon ran out, and I spent the rest of my visit sitting by her bedside, telling her what was new with Satchmo at the Waldorf and playing the songs she loved on my laptop.

The bare, banal words “failure to thrive” ran insistently through my mind as I looked upon her shrunken form. That, the doctors said, was what was wrong with my mother, pretending to explain what they could only describe. For months she had eaten less and less, then next to nothing. Though she assured us throughout the summer and fall that she wasn’t ready to die, she was no longer doing the one thing that might have made it possible for her to live. We understood: she was tired, and it was time.

I went home to New York knowing that I might be called back to Smalltown without warning. Thereafter I took care to keep my cellphone turned on and fully charged. I continued to call my mother every day or two, but most nights my brother would gently tell me that she was asleep, and finally I understood that there was no point in trying to speak with her any more. The time for talk was over.

* * *

As always, I threw myself into work in order to stave off despair. Going to the theater three or four nights a week was as good a way as any to keep my mind occupied, but in between shows I thought the same blunt, ugly thoughts that had come to me at odd moments ever since December. What do I do if she starts to fail while my play is in rehearsal? What’s the closest airport to Lenox? What if it happens on the morning of the dress rehearsal? Or on opening night? I drew up a string of increasingly far-fetched travel options, blithely ignoring the old saying I’d quoted a thousand times: if you want to hear God laugh, make a plan.

The day after the Broadway season ended, my wife and I stuck to one of our longest-standing plans and flew to Chicago so that I could review four shows there. Unlike the lightweight fare that I’d been seeing in New York, they were suited to my mood, at times joltingly so. To watch Angels in America or The Iceman Cometh while waiting for your mother to die is not an experience for the faint of heart.

The day after the Broadway season ended, my wife and I stuck to one of our longest-standing plans and flew to Chicago so that I could review four shows there. Unlike the lightweight fare that I’d been seeing in New York, they were suited to my mood, at times joltingly so. To watch Angels in America or The Iceman Cometh while waiting for your mother to die is not an experience for the faint of heart.

I called my brother from Chicago each night. He said the same thing every time: “She’s really weak, but the hospice nurses don’t think it’s going to happen right away.”

We returned to the East Coast on Friday and headed for our little farmhouse in Connecticut, hoping to spend the weekend getting some rest in preparation for what was to come. I was supposed to drive down to New Haven on Monday to be on hand when Long Wharf Theatre announced that Satchmo at the Waldorf would be produced there in October, but I had a feeling that this plan, unlike its predecessors, might be destined to go awry, and so it did. My brother called on Saturday night. “I think you’d probably better get here as soon as you can,” he said, sounding as weary as I felt.

It was too late to fly to St. Louis that night from anywhere in New England, so we stayed up until three in the morning, then went to the Hartford airport. A couple of hours later we flew down to Washington, changed planes for Memphis, picked up a rental car, and headed north toward Smalltown. As I drove, I thought of the day that my father died. I’d been in Washington on business, and by the time my brother called to summon me home, the last flight to St. Louis had left. I flew out the next morning and reached my father’s hospital room a half hour too late.

Ever since then I’d feared–assumed, really–that the same thing would happen when my mother died, and after I started covering regional theater performances throughout the country, I knew that it was now more than likely. This knowledge filled me with guilt, albeit of an ironic kind. My mother was fiercely proud of the things I did after I left home, but she also knew that it was leaving home that had made it possible for me to do them, and impossible for me to be with her more than occasionally. I never asked her if she thought I’d made the right choice. I think I was afraid of what she might say.

Ever since then I’d feared–assumed, really–that the same thing would happen when my mother died, and after I started covering regional theater performances throughout the country, I knew that it was now more than likely. This knowledge filled me with guilt, albeit of an ironic kind. My mother was fiercely proud of the things I did after I left home, but she also knew that it was leaving home that had made it possible for me to do them, and impossible for me to be with her more than occasionally. I never asked her if she thought I’d made the right choice. I think I was afraid of what she might say.

* * *

We got to the nursing home at one-thirty. The rest of the family had already gathered in my mother’s room. She was unconscious. A few muttered words from the hospice nurse told me all I needed to know. She was breathing rapidly and shallowly and her pulse was galloping. It could only be a matter of time before her heart gave out.

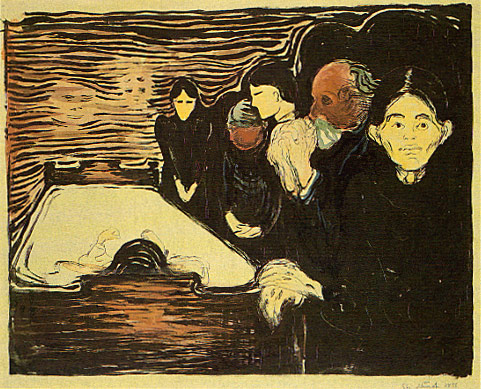

If you’ve never been present at the deathbed of a friend or family member, you might well be startled, even shocked, by what you see there. We have it on the best authority that humankind cannot bear very much reality, and no matter how despondent you may feel, it’s just as hard to stay stiff with sorrow for more than a few minutes at a time. Whispered confidences give way to more or less pleasant conversation, and if the death watch drags on long enough, there’s a good chance that you’ll hear a fair amount of laughter, some of which will almost certainly be yours. My journalist’s ear took in the laughter that day, just as my journalist’s eye saw that the TV in the corner of my mother’s room was tuned to a music channel, and that Frankie Valli was singing “Can’t Take My Eyes Off of You” as her minister prayed for her soul. Overly earnest artists are apt to scissor out such grotesque juxtapositions, but rare is the real-life deathbed scene at which they are nowhere to be found.

I laughed, too, but mostly I sat by the bed and watched my mother, stroking her hair and telling her that we all loved her, hoping against hope that she could hear my voice. Her suffering (if she was suffering, since she showed no sign of awareness) continued for several more hours, and though the nurses steadily increased the amount of morphine that they were giving her, it failed to relieve her all-too-visible respiratory distress.

Around nine o’clock the hospice nurse turned to my brother and me. As the room grew still, she explained that in order to bring my mother’s desperately labored breathing under control, she would have to administer a much larger dose. “If we do that, we don’t want you to be surprised by what might happen,” she said.

Around nine o’clock the hospice nurse turned to my brother and me. As the room grew still, she explained that in order to bring my mother’s desperately labored breathing under control, she would have to administer a much larger dose. “If we do that, we don’t want you to be surprised by what might happen,” she said.

The three of us looked at one another. My brother and I nodded in unison. “We understand,” I said. “Go ahead.”

Within a few minutes my mother was breathing much more slowly and easily, and everyone started talking again. I considered going to her house to try and get a few hours’ sleep. Then I noticed that her breathing had grown irregular. I gestured to the nurse. “Apnea,” she said. I decided to stay put.

I took my mother’s hand and told her for the hundredth time that we all loved her, watching her chest grow still, tremble briefly, then start to move again as she caught yet another shallow breath. My brother, our wives, and the nurse watched her no less intently, but no one else in the room seemed to notice what was happening. Her eyes were open for the first time that day, staring blankly at nothing. She seemed almost peaceful, and I felt no fear, only curiosity. I’ve never seen anyone die, I thought, continuing to hold her hand. What will it look like?

It looked like nothing at all. The next breath simply failed to come. I held my own breath in reflexive response, then let it out in a long sigh. A moment later, the nurse moved to the bed, put a stethoscope to her chest, and turned to me without saying a word. I nodded, stood up, kissed my mother’s forehead, and said, “I love you, darling. Goodbye.” I tried to close her eyes, the way I’d always seen it done in movies, but the lids wouldn’t shut.

When I turned away from the empty shell of the woman who gave me life, everyone around me was crying. My brother’s face, until then a rigid mask of self-control, was crumpled with grief. Only my eyes were dry. Under normal circumstances I am the easiest of weepers, but my own grief was buried deep beneath the stony rubble of exhaustion. Whatever I felt was, at least for now, inaccessible to me.

* * *

The next three days were hectic, but also familiar. My brother and I had buried my father, so we knew the routine. We went to the funeral home first thing in the morning to pick out a casket. My sister-in-law went through my mother’s closet and found the clothes in which she would be buried. I drove to the cemetery to arrange for her grave to be dug, got my hair cut and bought a new shirt and tie, then went back to the house to choose three songs to be played at the funeral on Wednesday.

My brother had already decided on the scripture that the minister would read, the Twenty-Third Psalm and the first eight verses of the third chapter of the Book of Ecclesiastes, the passage that begins To every thing there is a season, and a time to every purpose under the heaven. They were my mother’s favorites–she had marked them in her well-thumbed Bible–and none of us doubted that he had chosen wisely and well. The songs, somewhat to my surprise, were just as easy to choose. It took no more than a few minutes for me to settle on Aaron Copland’s sweetly austere version of At the River, the Monroe Brothers’ What Would You Give in Exchange for Your Soul, and a recording of Skylark by my old friend Nancy LaMott, at whose deathbed I had also been present sixteen years earlier. I liked the idea of hearing Nancy’s voice at my mother’s funeral, and even though “Skylark” is a love song, not a hymn, Johnny Mercer’s tender lyric seemed to me appropriate to the occasion: “In your lonely flight/Haven’t you heard the music of the night?”

Listening to the songs on my laptop, I began at last to sob uncontrollably. The sound of music had unlocked my heart. My wife put her arms around me. “I think maybe you’d better listen to those records a couple more times if you want to get through the funeral in one piece,” she said.

“I think you’re right,” I replied.

The list of necessary errands kept growing longer–it always does–but everything got done. Come Tuesday night we went back to the funeral home an hour before visitation was to begin. We had decided on Sunday that the casket would be closed to all but the immediate family. Even in the nursing home, my mother had always been meticulous about her appearance, and we knew that she wouldn’t have wanted any of her friends to see her looking the way she did in the last weeks of her life.

The list of necessary errands kept growing longer–it always does–but everything got done. Come Tuesday night we went back to the funeral home an hour before visitation was to begin. We had decided on Sunday that the casket would be closed to all but the immediate family. Even in the nursing home, my mother had always been meticulous about her appearance, and we knew that she wouldn’t have wanted any of her friends to see her looking the way she did in the last weeks of her life.

My own convictions on the matter were long settled. After reading The Loved One and The American Way of Death in high school, I’d decided that the “viewing” of a rouged corpse was a barbarous ritual, a belief hardened in adulthood by the way in which my father’s body was rendered unsightly beyond the possibility of repair by the rare skin cancer that killed him. Thus it astonished me when I entered the chapel, walked straight to the still-open casket, and saw that the undertaker, a kindly and unselfconsciously genial man who took his work with the utmost seriousness, had somehow contrived to erase all the brutal marks of suffering from my mother’s calm, ungarish face.

Everyone fell silent. “I think it would be all right to leave it open,” said Albert, my mother’s older brother. I heard an approving murmur from the rest of the family. Once more my brother and I looked at one another and saw that we were in unspoken agreement. “I think so, too,” I said, and again he nodded. It was the last thing I had ever expected to say, but I was taken aback by the rush of comfort that I felt at the sight of the familiar face that had been so carefully and sensitively restored, and I thought it right for others to feel it as well.

I touched her hand, then leaned over to kiss her forehead one last time. On Sunday it had been warm, but now it felt like a slab of marble. How could anyone who looked so alive be so chilly and still?

Soon the chapel was full. I knew that my mother had been greatly loved, but it still surprised me that so many mourners turned out that evening, and I spent the next few hours hugging people whom I hadn’t seen for years. Many of them came back the following afternoon for the funeral ceremony, and most of the ones who did accompanied us to the cemetery, where my mother’s minister, who had already spoken movingly of her goodness, said a few more words over her flower-covered casket. Then the family drove to the church, where a potluck supper awaited us.

It was the first time I’d eaten such a meal since the night that I dined on baked ham and hashbrown casserole in the fellowship hall of the small-town church where a young friend of mine had just gotten married. I thought of what I’d written about her wedding the next day:

I sat down again to watch my beloved friend embark on her new life. She looked flushed and radiant and determined, and I, perhaps not surprisingly, found myself tugged between hope for her future and curiosity about my own. The time between Thanksgiving and Christmas is uncomfortable for me at best, and I’d been at loose emotional ends for the past couple of weeks….Now I was sitting in a place redolent of my long-ago youth, at once utterly alien and utterly familiar, feeling not unlike the Marschallin in Der Rosenkavalier, who wandered through her palace at midnight, stopping all the clocks, trying to turn her back on time.

Like time itself, all things must pass, and just as my friend’s marriage came apart a few years later, so had my mother’s long, mostly happy life reached its sad and painful end. Yet here we all were, joking and laughing and eating hashbrown casserole in the fellowship hall of yet another small-town church. The clocks had started again.

* * *

Two days later my wife and I were back in New York, and two days after that we flew to California to spend a couple of weeks seeing shows. I wondered how long it would be before I set foot in Smalltown again, and how much time would go by before my mother’s death felt fully real to me.

The following week we drove down Highway 1 from Santa Barbara to Los Angeles, passing by a seemingly endless string of strip malls. I’ve never seen a place as rootless as this, I thought.

The following week we drove down Highway 1 from Santa Barbara to Los Angeles, passing by a seemingly endless string of strip malls. I’ve never seen a place as rootless as this, I thought.

“You know how I feel today?” I asked my wife. “Empty. Absolutely empty. Like my taproot had been torn out of the ground.”

“I think I know what you mean,” she said, reaching out to squeeze my arm.