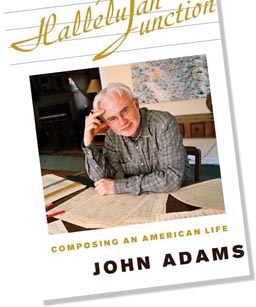

I regret to say that I didn’t see Doctor Atomic, John Adams’ new opera, when it came to the Metropolitan Opera last month. I had plays to review or was out of town throughout its too-short run. I did, however, pick up a copy of Adams’ Hallelujah Junction: Composing an America Life, which was published a couple of months ago, and found it to be both readable and immensely interesting. Truth to tell, I can’t think of a better memoir by a major American composer–and Adams undoubtedly qualifies as major, even though his minimalist music has never been my cup of tea. He’s already made a deep impression on postwar American opera, and now that Paul Moravec and I are writing an opera of our own, it stands to reason that I’d take an interest in what Adams has to say in Hallelujah Junction about his own stage works.

I regret to say that I didn’t see Doctor Atomic, John Adams’ new opera, when it came to the Metropolitan Opera last month. I had plays to review or was out of town throughout its too-short run. I did, however, pick up a copy of Adams’ Hallelujah Junction: Composing an America Life, which was published a couple of months ago, and found it to be both readable and immensely interesting. Truth to tell, I can’t think of a better memoir by a major American composer–and Adams undoubtedly qualifies as major, even though his minimalist music has never been my cup of tea. He’s already made a deep impression on postwar American opera, and now that Paul Moravec and I are writing an opera of our own, it stands to reason that I’d take an interest in what Adams has to say in Hallelujah Junction about his own stage works.

What struck me most forcibly about Adams’ account of the genesis of Doctor Atomic is that it bears no resemblance whatsoever to the way in which Paul and I have gone about writing The Letter. The differences are so vast, in fact, that it scarcely seems as though we’re working in the same genre as Adams and Peter Sellars, who wrote–or, rather, compiled–the libretto for Doctor Atomic, a patchwork tapestry drawn from official documents, interview transcripts, and the poetry of Baudelaire, John Donne, and Muriel Rukeyser.

Most critics have been lukewarm at best about Sellars’ libretto, and some wrote quite sharply about it. But music critics, even those who cover opera regularly, tend not to think in specifically stage-oriented terms, and I haven’t read any reviews of the opera that cut to what I suspect was the heart of the matter, which is that Doctor Atomic, at least on paper, sounds more like an oratorio than an opera.

In works like Handel’s Messiah or Benjamin Britten’s War Requiem, which are specifically intended for the concert hall rather than the stage, the singers and chorus describe and comment on dramatic situations rather than enacting them. From time to time opera companies attempt to put such essentially static works on stage–the Metropolitan Opera recently did just that with Berlioz’s Damnation of Faust–but these presentations usually end up amounting to little more than a series of visually striking tableaus accompanied by music. The results may be interesting to look at, but they don’t move. Road Show, Stephen Sondheim’s new musical, is something like that. I described it in my Wall Street Journal review as “all tell and no show, a string of talky, undramatic ensemble numbers that feels more like an oratorio than a musical.”

Might it be that Doctor Atomic suffers from a similar lack of dramatic momentum? Having read Hallelujah Junction, my guess is that this deficit, if such it be, didn’t trouble John Adams in the slightest. His operas are intended to function not as conventional stage dramas but as mytho-poetical statements that are illustrative of larger ideas about the condition of man. Doctor Atomic, for instance, attempts to retell the Faust myth in specifically American terms, with J. Robert Oppenheimer, the scientist who directed the research-and-development program that led to the building of the first atomic bomb, cast in the role of the all-too-human genius who sells his soul and lives to regret it.

Might it be that Doctor Atomic suffers from a similar lack of dramatic momentum? Having read Hallelujah Junction, my guess is that this deficit, if such it be, didn’t trouble John Adams in the slightest. His operas are intended to function not as conventional stage dramas but as mytho-poetical statements that are illustrative of larger ideas about the condition of man. Doctor Atomic, for instance, attempts to retell the Faust myth in specifically American terms, with J. Robert Oppenheimer, the scientist who directed the research-and-development program that led to the building of the first atomic bomb, cast in the role of the all-too-human genius who sells his soul and lives to regret it.

In Hallelujah Junction Adams says matter-of-factly that Peter Sellars’ libretto “was unlike anything the opera world had ever encountered,” elsewhere implying that his musical setting of the words compiled by Sellars is theatrically problematic:

Doctor Atomic will never be an easy addition to the standard repertoire. The long, dreamlike second act will always present a challenge for directors and conductors. Where act I follows a more or less logical narrative thread, act II is a nearly ninety-minute symphonic arch that oscillates back and forth between a real-time event…and a willfully abstracted treatment of time and space that is part dream vision and part sudden, terrifying apparition.

All of which sounds fascinating, but not dramatic in the traditional sense of the word–though I hasten to point out that in the world of drama, there are many, many ways to skin a cat. Theater, as I have written elsewhere, is “an empirical art whose practitioners make their own rules.” It is, first and foremost, about what works, and the fact that four major opera companies have produced Doctor Atomic to date suggests that it works.

The Letter is meant to work in another kind of way, one that arises in part from my experience as a critic who has spent much of his life looking at and writing about stage works of various kinds, opera very much included. This experience has taught me four things:

• Repertory opera is about emotions, not ideas. Thus the most important part of an opera libretto is not the language in which it is written but the dramatic gestures it makes. If the plot is involving and the music powerful, nobody will notice the words.

• Most repertory operas are structured like plays. They are plot-driven, not meditative. Even when they contain fantastic occurrences, the characters respond to them in a recognizably human way.

• On the other hand, opera is not a naturalistic medium, since the characters sing instead of speaking. This means that the libretto of a repertory opera cannot be written in straight prose. As Paul explained at the press conference in Santa Fe at which the cast and production team for The Letter were announced, “Terry’s goal in writing the libretto was to take a prosy, naturalistic play and make it operatic, which means making it lyrical. That’s what makes it singable. Opera is about heightened, larger-than-life emotions. If it isn’t, there’s no reason why the characters should be singing.”

• Conversely, elaborately poetic language is usually superfluous and may even get in the composer’s way. It’s his job, not the librettist’s, to create the poetic atmosphere of an opera.

These “rules” are normative, not absolute. I can think of any number of well-known operas that break one or more of them, and some of those operas–Capriccio, Four Saints in Three Acts, and The Midsummer Marriage come immediately to mind–are among my favorites. But none of them is popular. They have remained on the fringes of the repertory and are rarely revived.

Paul and I, by contrast, set out to write a repertory-style opera, one to which everyday operagoers would respond as readily as connoisseurs or intellectuals. As the librettist, it was my job to create the conditions under which Paul could compose such an opera. (I like to refer to myself as his “enabler.”) Once he suggested that we might look to the works of Somerset Maugham for source material, I came up with the idea of adapting The Letter, a “well-made” stage play that was a hit in London and on Broadway and was later turned into an equally successful movie. Like most repertory operas, The Letter is devoid of Big Ideas–the passionate emotions of the characters are its subject matter–and the libretto is lyrical but for the most part not explicitly poetic.

Some people will doubtless conclude from this bald description that The Letter is less ambitious than Doctor Atomic, but I prefer to think that Paul and I have different ambitions for it. Is Rigoletto less ambitious–or less serious–than Götterdämmerung? No more, surely, than The Great Gatsby, with its melodramatic plot and novella-like scale, is less serious than War and Peace.

Asked to compare his operas to those of Benjamin Britten, Michael Tippett, the composer-librettist of The Midsummer Marriage, replied that Britten was trying to create an English equivalent of verismo, the Italian style of operatic realism, while his own myth-based stage works were about “magic.” Paul and I have never denied that the The Letter, like Britten’s Peter Grimes, is at bottom a verismo opera. But as Miles Davis reportedly said to a journalist who accused him of having once been a pimp, “Wuz wrong with that?”

Asked to compare his operas to those of Benjamin Britten, Michael Tippett, the composer-librettist of The Midsummer Marriage, replied that Britten was trying to create an English equivalent of verismo, the Italian style of operatic realism, while his own myth-based stage works were about “magic.” Paul and I have never denied that the The Letter, like Britten’s Peter Grimes, is at bottom a verismo opera. But as Miles Davis reportedly said to a journalist who accused him of having once been a pimp, “Wuz wrong with that?”

I love Tippett’s music, but if I had to choose between The Midsummer Marriage and Peter Grimes–or between War and Peace and Gatsby, for that matter–I wouldn’t hesitate for a moment before picking the latter. Nor would I think less of anyone else for making the opposite choice. Like I said, there’s more than one way to skin a cat.