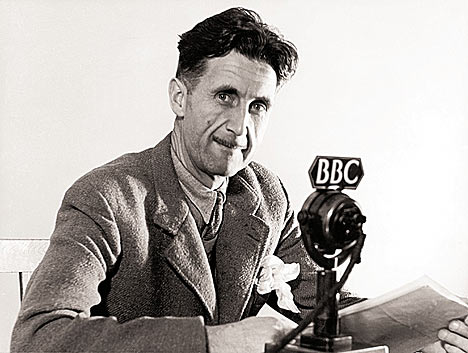

I read Paul Collins’ article in Slate about the decline and fall of the semicolon with interest and amusement. I confess, though, that the first thing I did was search through the piece for George Orwell’s name. While Orwell was mentioned in passing, Collins failed to include the wonderfully trivial fact that the author of Nineteen Eighty-Four claimed to have written an entire novel, Coming Up for Air, that contains no semicolons whatsoever. “I had decided about this time that the semicolon is an unnecessary stop and that I would write my next book without one,” he explained in a letter to Roger Senhouse.

But did he succeed? It’s been years since I last read Coming Up for Air, and I didn’t collate it for semicolons on that occasion. Since then a searchable e-text of the book, which was published in 1939, has been posted by Project Gutenberg, and no sooner did I start trolling for the allegedly superfluous punctuation mark than I found this characteristic passage, in which Orwell’s narrator describes a nasty little diner to which he paid a visit in search of an edible meal:

Behind the bright red counter a girl in a tall white cap was fiddling with an ice-box, and somewhere at the back a radio was playing, plonk-tiddle-tiddle-plonk, a kind of tinny sound. Why the hell am I coming here? I thought to myself as I went in.There’s a kind of atmosphere about these places that gets me down. Everything slick and shiny and streamlined; mirrors, enamel, and chromium plate whichever direction you look in. Everything spent on the decorations and nothing on the food. No real food at all. Just lists of stuff with American names, sort of phantom stuff that you can’t taste and can hardly believe in the existence of. Everything comes out of a carton or a tin, or it’s hauled out of a refrigerator or squirted out of a tap or squeezed out of a tube. No comfort, no privacy. Tall stools to sit on, a kind of narrow ledge to eat off, mirrors all round you. A sort of propaganda floating round, mixed up with the noise of the radio, to the effect that food doesn’t matter, comfort doesn’t matter, nothing matters except slickness and shininess and streamlining. Everything’s streamlined nowadays, even the bullet Hitler’s keeping for you. I ordered a large coffee and a couple of frankfurters. The girl in the white cap jerked them at me with about as much interest as you’d throw ants’ eggs to a goldfish.

Damn.

Having found that a cherished literary myth was nothing more than that, I searched the rest of Coming Up for Air and located four more semicolons. I was shocked–shocked! Maybe Louis Menand was right after all.

Having found that a cherished literary myth was nothing more than that, I searched the rest of Coming Up for Air and located four more semicolons. I was shocked–shocked! Maybe Louis Menand was right after all.

As for me, I rarely use semicolons in my own writing. This is not a quirk: I’ve spent years cultivating the art of writing the way I talk, and you can’t really “speak” a semicolon out loud. (Maybe John Gielgud could, but I can’t.) So I eschew them–usually. I can’t remember the last time I used one in a Wall Street Journal column. The manuscript of Rhythm Man: A Life of Louis Armstrong, which is 175,000 words long, contains no more than one or, at most, two semicolons per chapter, not counting those that appear in quotations from other writers. Several chapters are entirely semicolon-free.

For what it’s worth, here’s an example of how I used the semicolon in Rhythm Man:

For all his virtuosity, Armstrong was never at his best when playing at fast tempos. It was in ballads, swinging medium-tempo numbers, and the blues that he did his most creative improvising. If he had recorded nothing but “Star Dust” and “St. Louis Blues,” he would still be remembered as the greatest jazz soloist of his time; if he had recorded nothing but “Chinatown, My Chinatown” and “I Got Rhythm,” he would be remembered only as a high-note specialist with a funny voice.

And yes, you can say that one out loud. Try it.