Moss Hart, who grew up poor and spent a not-inconsiderable portion of his young life riding the subway from deepest Brooklyn to Times Square, swore that if he ever struck it rich, he’d take cabs everywhere, even if his destination was only a block or two away. I’ve never been poor and have yet to strike it rich, but I rode the subway often enough in my first years as a New Yorker to be glad that I can now afford to take cabs. Be that as it may, a true New Yorker who wants to get somewhere at ten on a rainy morning takes the subway, and since today’s Mass for the repose of the soul of William F. Buckley, Jr., who died five weeks ago, was scheduled to start at ten o’clock sharp at St. Patrick’s Cathedral, I put on my black outfit and raincoat, descended into the bowels of Manhattan, and made my bumpy way to the Rockefeller Center station in the midst of a rush-hour crowd.

It’s been quite a while since I walked through Rockefeller Center, even longer since I crossed Fifth Avenue and went inside St. Patrick’s, and a very long time indeed since I last attended a memorial service for a public figure. For all these reasons, I have no standard against which to measure Bill’s funeral obsequies. All I can tell you was that today’s service seemed as splendid as it could possibly have been. The cathedral was full of mourners, the choir loft full of singers, and the music was mostly appropriate to the occasion. Bill was a serious amateur musician who loved Bach above all things–he actually performed the F Minor Harpsichord Concerto in public on more than one occasion–so the organist played “Sheep May Safely Graze” and the slow movement of the Toccata, Adagio, and Fugue in C Major. No less suitable were the sung portions of the Mass, drawn from Victoria’s sweetly austere Missa “O magnum mysterium,” and the closing hymn, the noble tune from Gustav Holst’s The Planets to which the following words were later set: I vow to thee, my country–all earthly things above–/Entire and whole and perfect, the service of my love.

It’s been quite a while since I walked through Rockefeller Center, even longer since I crossed Fifth Avenue and went inside St. Patrick’s, and a very long time indeed since I last attended a memorial service for a public figure. For all these reasons, I have no standard against which to measure Bill’s funeral obsequies. All I can tell you was that today’s service seemed as splendid as it could possibly have been. The cathedral was full of mourners, the choir loft full of singers, and the music was mostly appropriate to the occasion. Bill was a serious amateur musician who loved Bach above all things–he actually performed the F Minor Harpsichord Concerto in public on more than one occasion–so the organist played “Sheep May Safely Graze” and the slow movement of the Toccata, Adagio, and Fugue in C Major. No less suitable were the sung portions of the Mass, drawn from Victoria’s sweetly austere Missa “O magnum mysterium,” and the closing hymn, the noble tune from Gustav Holst’s The Planets to which the following words were later set: I vow to thee, my country–all earthly things above–/Entire and whole and perfect, the service of my love.

The only thing that made my inner critic smile wryly was the performance during communion of the Adagio in G Minor long attributed to Albinoni but in fact woven out of whole cloth by one Remo Giazotto. It is a preposterously operatic piece of spurious yard goods, and to hear it played on the organ with all stops pulled put me in mind of something Bill wrote after attending a Virgil Fox recital many years ago:

At one point during a prelude, I am tempted to rise solemnly, commandeer a shotgun, and advise Fox, preferably in imperious German, if only I could learn German in time to consummate the fantasy, that if he does not release the goddam vox humana, which is oohing-ahing-eeing the music where Bach clearly intended something closer to a bel canto, I shall simply have to blow his head off.

That was the Bill Buckley I knew, whip-smart and impishly outrageous, the same man that David Remnick had in mind when he described Bill as having “the eyes of a child who has just displayed a horrid use for the microwave oven and the family cat.”

I wish I could say I knew him well, but I didn’t. I dined at his table a number of times but was only alone with him once, when I interviewed him about Whittaker Chambers for an anthology of Chambers’ journalism that I edited in 1989. On that occasion Bill assured me that although they had been close, Chambers never had “any direct historical or intellectual influence” on him. The reason he gave is striking:

I never embraced, in part because subjectively it’s contra naturam to me, that utter, total, objective, strategic pessimism of his. Among other things, I think it’s wrong theologically to assume that the world is doomed before God decides to doom it. So I never drank too deeply of his Weltschmerz.

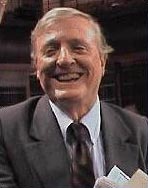

Indeed he did not: Bill was the least weltschmerzy person imaginable. Henry Kissinger, who eulogized him this morning, alluded to that side of Bill’s personality when he remarked that Bill “was vouchsafed a little miracle: to enjoy so much what was compelled by inner necessity.” I couldn’t have put it better. Bill worked fearfully hard and was deadly serious about what he believed, but he extracted self-evident enjoyment from everything he did, and you couldn’t be in his presence for more than a minute or two without responding to his joie de vivre. If I’d been in charge of the music today, I would have made a point of picking something a good deal more festive–Bach’s Fugue à la gigue, say, or one of the harpsichord sonatas in which Scarlatti turned Bill’s favorite instrument into a giant super-guitar.

Indeed he did not: Bill was the least weltschmerzy person imaginable. Henry Kissinger, who eulogized him this morning, alluded to that side of Bill’s personality when he remarked that Bill “was vouchsafed a little miracle: to enjoy so much what was compelled by inner necessity.” I couldn’t have put it better. Bill worked fearfully hard and was deadly serious about what he believed, but he extracted self-evident enjoyment from everything he did, and you couldn’t be in his presence for more than a minute or two without responding to his joie de vivre. If I’d been in charge of the music today, I would have made a point of picking something a good deal more festive–Bach’s Fugue à la gigue, say, or one of the harpsichord sonatas in which Scarlatti turned Bill’s favorite instrument into a giant super-guitar.

Christopher Buckley, Bill’s son, followed Henry Kissinger, and gave just the sort of eulogy I’d expected from him, funny and light-fingered, putting much-needed smiles on our faces. Only at the end did he sound a darker note, quoting the lines from Robert Louis Stevenson’s “Requiem” that he chose as the epitaph for a man who loved sailing as much as he loved Bach: Here he lies where he long’d to be;/Home is the sailor, home from the sea,/And the hunter home from the hill. Then we all sang “I Vow to Thee, My Country,” pushed our way past the waiting photographers, and returned to the gray, misty day.

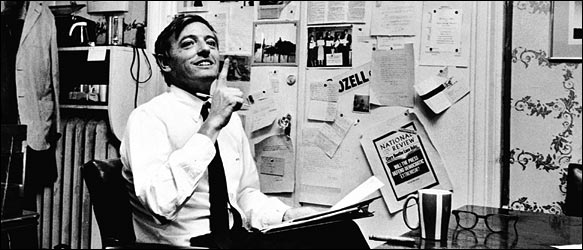

I passed up a lunch invitation and went home by myself, preferring to be alone with my thoughts. I was thinking of an evening in the fall of 1985, not long after I moved to New York from the Midwest. I’d been writing for National Review, Bill’s magazine, since 1981, but I’d never met my first great patron face to face, so he invited me to an editorial dinner at his Park Avenue apartment. Back then I was working for Harper’s, whose offices were in Greenwich Village, and the thought of meeting Bill for the first time was so exciting that I walked all the way from Astor Place up to 73 East 73rd Street (where Bill invariably entertained at 7:30).

It was, of course, a symbolic gesture: I was taking possession of the streets of the city to which I had moved and in which I hoped someday to make a name for myself. At the end of my journey I knocked on the door of Bill’s maisonette, and a few moments later he clasped my hand and said, “Hey, buddy!” It was, I would learn, his standard greeting, always uttered with a warmth that remained disarming no matter how often you basked in it.

Ever since then I have associated Bill Buckley with New York, whose doors he flung wide to me, just as he opened the pages of the magazine he edited. Now New York is my home–but Bill is gone, buried in Connecticut, home at last from the sea. Somehow you never imagine outliving the people who show you through the doors that lead to the rest of your life.